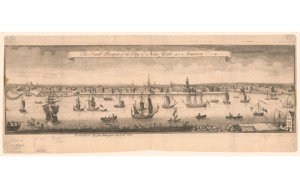

“The south prospect of the city of New York in America,” William Burgis, 1717, reissue by Thomas Bakewell, 1746, Library of Congress

On August 5, 1717, Captain Richard Vivian anchored the sloop John and Anne in the port of New York City on the East River.[1] The sailors on board entered a lively port engaged in trade from deep in the interior of North America to the edges of the Atlantic. Looking to their left at the city of about 6,500 people, they saw Fort George at the southern end of Manhattan, paved streets, a shipyard, wharves and slips on the river, brick and stone houses, Trinity Church, storehouses, markets, taverns, inns, the King’s Arms coffeehouse, City Hall with a new clock in its tower, then Maiden Lane and the commons.[2]

The people of colonial New York City were from across the Atlantic and nearby settlements.[3] There were early Dutch settlers and English merchants, French Huguenots from La Rochelle, and Jewish families from London, Suriname, and Curaçao.[4] Sailors and traders from other colonies and Spain, Portugal, and Africa came through the port. The Lenape, Montauk, and Mahican people traded with the settlers, who depended on a military alliance with the Iroquois.[5] Charles Lodwick, a future mayor, wrote in 1692 that “Our chiefest unhappyness here is too great a mixture of nations” and “As to religion, we run so high into all opinions, that here is, (I fear,) but little reall.”[6]

The ship came from Nevis, an island in the Caribbean with an important port for Atlantic trade, and its cargo included sugar, molasses, and coconuts. The merchant Abraham De Peyster, the twenty-first mayor of New York City from 1691 to 1694, was one of the owners of the ship and perhaps the wealthiest man in the city.[7] He donated the land for the construction of the new city hall in 1700 and his “lofty brick and stone buildings” near the docks contained goods imported from the Caribbean and Europe, including wines.[8]

But commerce in New York included human bondage. On board there were enslaved people purchased on Nevis, perhaps destined for the slave market near the edge of the river or to be sold before they left the ship.[9] And, De Peyster, like other wealthy New Yorkers, owned enslaved people who were part of his household near the East River.[10] The boatmen who took the cargo of ships to the docks in smaller vessels were enslaved, and enslaved men built much of the city, from the fort to the roads and houses.[11] There were about one thousand enslaved people in the city at this time and for parts of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, New York City had more enslaved people than any other city in North America.[12]

Dutch Rule and Slavery

From its beginning as a European colony, Manhattan was a commercial venture, but it was far from the center of world trade. The Dutch West India Company, a joint stock venture owned by European merchants and the legislature of the Dutch Republic, sent colonists to the island in 1624 and viewed it as one of its many trading posts.[13] The company focused on more lucrative prospects, including the fur trade near today’s Albany and seizing ships and plantations from rival powers in the Caribbean and South America. Officials of the company in the town they named New Amsterdam oversaw a vast trading empire through Curaçao, built immense personal fortunes, and depended on enslaved workers to build the streets and fortifications and to work in the fields.[14]

Slavery came very shortly after the first settlers. In 1627, the company ship Bruynvisch arrived with twenty-two enslaved Africans.[15] But even before the company, Europeans were involved with slavery on Manhattan. There is a recorded instance of Europeans taking captives from the area in 1525 and the first non-Indigenous resident of Manhattan, Jan Rodrigues in 1613, was formerly an enslaved man. By the late 1630s, there were about one hundred enslaved men and women in New Amsterdam, amounting to one-third of the population.

In 1644, enslaved people were granted conditional freedom if they paid an annual fee to the Dutch West India Company and worked for the company. However, their children were born enslaved and had to serve the company. By the end of Dutch rule in 1664, about seventy-five out of about three hundred and seventy-five Black people in New Amsterdam were free. And, in the middle of the seventeenth century, Black men and women had become part of New Amsterdam society.[16]

However, company officials expanded the slave trade over time and came to encourage merchants to invest in slave ships. The enslaved people on the Bruynvisch were captured from a Portuguese ship by privateers, who had official sanction to seize the ships of rival powers and sell enslaved people.[17] In 1655, the Witte Paert arrived with 391 captives, the first direct voyage of captive Africans directly to New Amsterdam.[18] The final Dutch West India Company investment in the slave trade to New Amsterdam was the Gideon, which sailed from Amsterdam in November 1663 and purchased 421 captives in West Africa.[19] After selling some captives in Curaçao, Gideon arrived in New Amsterdam on August 15, 1664 with 290 enslaved people.[20]

Merchant Political Power in New York

On August 26, 1664, Richard Nicolls arrived in the harbor on an English warship to seize the Dutch colony while Gideon was still anchored close to town. Three more English warships arrived two days later. As England took control of the colony, the sale of the captives at auction in town proceeded. Auctions took place on August 30 and September 1. On September 8, Peter Stuyvesant surrendered to the English. Four days later the final auction of the enslaved on the Gideon took place.[21]

The September 1664 transfer of power from the Netherlands to England was unique: a peace that kept commerce intact. During that month, six English and six Dutch officials negotiated articles that enumerated rights for the Dutch, as they became denizens of New York who could keep their property, including their ships, and continue to trade. Richard Nicolls became the first Governor of New York, but his appointments of New York City officials included Dutch and English men. Nicolls also ordered that the final sale of captives from the Gideon could take place but none of the proceeds went to the Dutch West India Company. [22]

Three wealthy merchants, all enslavers, show the continuity of Dutch commercial and political power. In 1653, New Amsterdam had its first municipal government: two burgomasters (similar to mayor) and five schepens (alderman and judge) were appointed by Director-General of New Netherland Peter Stuyvesant and his council to annual terms. Oloff Van Cortlandt and Cornelius Steenwyck were among the six Dutch officials who negotiated the transfer of power.[23] At the time, Steenwyck was a burgomaster and Van Cortlandt formerly held the office seven times.[24] Van Cortlandt served in many positions in the new city’s government and two of his sons served as mayor.[25] Steenwyck was later appointed mayor twice and both men had fortunes that grew under English rule.

The third merchant, Thomas Willett, was an English captain in the Plymouth Colony militia. Beginning around 1640, he traded with New Amsterdam on behalf of Plymouth Colony and purchased a small fleet of ships to facilitate this trade and for private profit.[26] On June 12, 1665, Governor Nicolls appointed Willett the first mayor of New York City and Van Cortlandt one of the five aldermen of the city.[27]

The Duke’s Map of New York, 1664, British Library

Early Mayors

English royal governors appointed men who were often the wealthiest merchants in the city as mayor. Until 1703, mayors were usually appointed for a one-year term that began in October. After that, mayors mainly served four-year terms, with some up to ten years.

Forty-nine men served as mayor, including two acting mayors, until enslaved people were emancipated in New York in 1827. Of those, forty-three—about 88%—are documented enslavers or direct investors in the slave trade. Looking at mayoral terms, from 1665 to 1827 there are a total of 163 years of mayors in office. For 158 of those years, there is a documented enslaver in office for at least part of the year, which is about ninety-seven percent of the time. The other six mayors could have been enslavers or investors in ships that carried the enslaved, but the evidence of personal ownership is lacking. However, as mayor they enforced slave codes and regulated slave sales as part of their official duties.

Willett and most of the early mayors were merchants who built family fortunes from trade, agriculture, land, and the slave trade. Some mayors exported wheat, rye, and corn to the Caribbean and received enslaved people, sugar, cotton, and fruit as payment. The mayors also bought logwood from the Caribbean, tobacco from the southern colonies, and fur from the Hudson and Delaware valleys, which was part of a large network of trade with Indians. They exported sugar, fish, and agricultural products to Europe and imported clothes, luxury goods, and wine in return. Some even engaged in piracy and smuggling.[28]

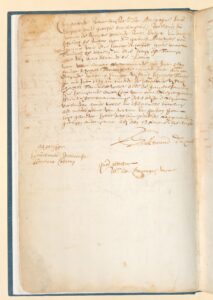

At this time, slave sales included auctions and could be paid for in pelts, commodities, or animals. In April 1667, William Beekman (an acting mayor) sold enslaved persons for fifty-five beaver skins.[29] In November 1676, Sixteenth Mayor Gabriel Minvielle sold an enslaved man named Prince for three hundred schepels of wheat and an enslaved boy for cash and 855 pounds of sugar.[30]

Mortgage after Prince sold for wheat, November 13, 1676, Ulster County Archives

The arrival of the sloop John and Anne in 1717 is the first recorded landing of a ship owned by a mayor that directly transported the enslaved into New York’s port. However, five mayors engaged in the slave trade from Africa decades before. Fourth and Fifteenth Mayor Cornelius Steenwyck was an investor in three ships that sailed from 1667 to 1669—two of them while he was mayor—and Seventeenth Mayor Nicholas Bayard was an investor in one of those ships, which sailed from Adra on the Bight of Benin in Africa to Curaçao with captives.[31]

At least three mayors were investors in the illegal slave trade with Madagascar and other parts of the Indian Ocean, which flourished in the 1690’s and avoided the Royal African Company’s monopoly over slavery in West Africa. This slave trade was supported by New York colonial governors who received money from pirates who took enslaved people and cargo from areas often under the control of the East India Company and brought them to the Caribbean or North American colonies.[32] Thirty-Second Mayor Caleb Heathcote co-owned the Nassau, which left New York on July 7, 1698.[33] In May of the following year, it anchored in Cape May and Sandy Hook to offload enslaved people, cargo, and passengers to avoid seizure by customs officials, while finally beaching at Red Hook.[34] Officials intercepted a letter from the captain to the other owner of the ship. The captain wrote that the cargo of the Nassau included twenty-three enslaved people, about seventy pirates returning from Madagascar, and fare from the passengers.[35]

The colonial mayors had executive powers, including issuing payments and presided over the Common Council, which enacted and enforced laws. Mayors had the power to commit those suspected of crimes to jail and the exclusive right to issue licenses to taverns and inns and kept the license fees.[36] Mayors were also responsible for keeping lists of visitors, which were provided by constables and ship captains.[37] The council often approved laws unanimously but when it voted mayors presided but did not vote. The early mayors also served as the presiding judge of the Mayor’s Court, which heard minor civil and criminal cases. Aldermen and the city recorder, who presided over the mayor’s court, sat on the council, and many of the mayors also served as aldermen.[38] There were elected officials at the ward level, including constables, assessors, and aldermen.[39]

Depiction of first City Hall: “The Stadthuys of New York in 1679 corner of Peal St. and Coentijs Slip,” 19th centurty, NYPL

Almost two-thirds of early council members were merchants and most of their efforts were to oversee trade.[40] In 1707, over half of the Common Council ordinances dealt with commerce, including constructing the waterfront and market houses; ferries to Long Island; standards for weights and currency, adjusting market prices for goods, and licensing and restricting the number of tradespeople.[41] The mayors and council granted legal status to enact trade or work as an artisan, freemen, and later, freeholders (landowners), and collected revenue through fees or leases of city property.[42]

They also passed slave codes. Under English colonial rule, there were fewer opportunities for free Blacks and additional slave codes. The first laws of the colony, the Duke’s Laws, officially recognized slavery.[43] In April 1691, Seventh (and later Twentieth) Mayor John Lawrence presided as the council ordered “every Male Negro in the Citty with Wheele barrows and Spades performe one dayes Worke” per week on water lots, parcels of land on the waterfront that the city sold on the condition that the shore would be extended and wharves would be built.[44] In 1702 the Province of New York implemented its first comprehensive slave codes and in 1706 enacted a law that defined slavery as a racial category: the children of enslaved Black, Indian, or mixed ancestry mothers were born enslaved.[45] By the time New York enacted another slave code in in 1712 that prohibited newly free people from property ownership, most free Blacks left New York City.[46]

In March 1712, Mayor Caleb Heathcote presided as the council enacted “A Law Appointing a Place for the More Convenient Hiring of Slaves.” It stated that “all Negro Mulatto and Indian slaves that are lett out to Hire within this City do take up their Standing, in Order to be Hired, at the Markett House at the Wall Street Slip untill such time as they are hired…”[47] Enslavers in New York City often allowed others to hire their enslaved people for a day or weeks at a time to produce additional income.[48]

The Mayor’s Court enforced punishment against the enslaved. In February 1680, Mayor Gabriel Minvielle brought a case against his enslaved woman “called Danielle for drawing his knife” against a “Burger of this Citty and rideing in a Cart contrary to the orders of this Citty, and several other Misdemeanors…” The punishment was “forty Lashes at the Whipping post” and Danielle to pay court costs.[49]

At the beginning of the 1700’s, over forty percent of European households in the city had enslaved people, who were more than a quarter of the labor force.[50] Enslaved people usually stayed in the backrooms, cellars, or garrets of houses in the city so there was little space in cramped quarters.[51] Most enslaved people lived with one other person or by themselves, which was the case for many enslaved women.[52] Ebenezer Wilson had one enslaved woman and one enslaved man in his house.[53]

However, the mayors, like other successful merchants, had many enslaved persons. A traveler in 1697 noted that Abraham De Peyster had a “noble building of the newest English fashion and richly furnished with hangings and pictures.” This house had nine enslaved people: two women, two girls, and five men.[54] Philip French, whose fortune came from piracy, trade, and land, had seven enslaved people: two women, three men, and one boy and one girl, in his house near the docks.[55]

Only about a quarter to a fifth of the enslaved people brought into the port remained in New York City and the rest were sold to farmers.[56] While many farmers had a few enslaved persons, there were some plantations. Caleb Heathcote had ten enslaved people on his estate in Scarsdale that had slave quarters.[57] Gerrardus Stuyvesant had nineteen enslaved people, many of whom worked on the large Stuyvesant farm, on today’s East Village.[58]

The Van Cortlandt brothers Stephanus and Jacobus created fortunes as merchants, sold enslaved people, both served twice as mayor (Stephanus was the eleventh and eighteenth mayor while Jacoubs was the thirty-first and thirty-fourth), and owned vast estates. In 1690, Stephanus invested in a ship that purchased enslaved people from Madagascar.[59] Jacobus had enslaved people who did domestic chores, grew wheat, maintained roads, built barns, and operated two mills.[60] Jacobus sold enslaved persons to nearby farmers on consignment, and his estate is today’s Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx.[61] In a June 4, 1690 letter, he complained about “the great quantity of slaves that are come from Madagascar” because they made the “slaves to sell very slow.”[62]

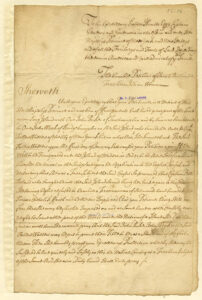

Enslaved persons were not allowed to give evidence against colonists or free persons. However, there are petitions from two enslaved persons against mayors. While the petitions are in the legal language of the time, there is still room for the enslaved to tell their story. Sarah Robins was enslaved by Thirty-Fifth Mayor Robert Walters and in September 1711, she petitioned Governor Robert Hunter for her freedom. Her petition described her “a free Indian woman” who lived in Southampton but “…Robert Walters upon the first day of January last caused your Petition[er] against her will to be Transported unto the Island of Madeira in Order to be there sold for a slave.” Upon arriving in Madeira, then a Portuguese colony, Sarah petitioned a British official and was returned to New York. It is unclear what happened to Sarah or her case.[63]

“Petition of Sarah Robins, a Free-born Indian Woman,” 1711, NY State Archives

In another petition to the governor, Sam, a free Black man, asked for the freedom of Robin, who was enslaved. Sam was enslaved by George Norton, who freed him in his 1715 will. Norton also granted Sam thirty pounds and Robin, another enslaved man. However, Norton named Thirtieth Mayor Ebenezer Wilson as the sole executor of his will and trustee. Wilson kept Robin and the money. In September 1717, Sam stated that Wilson “detains money and a negro willed to him by said Norton yet requires the petitioner to clothe said slave and support him in sickness.”[64] It is uncertain what happened to Sam.

1712 Uprising

On April 7, 1712, recently arrived African enslaved people, likely from Akan-Asante society, led an uprising. Slavery in New York City was unlike their society, which had a defined relationships in slavery and laws for the just treatment of the enslaved.[65] Other enslaved people considered themselves free Spanish citizens and who deserved the privileges and freedom they had under the Dutch.

Twenty-three enslaved people and an unknown number of Indigenous peoples armed with guns, hatchets, and swords set fire to a building in New York City. At least nine colonists were killed and six wounded when they tried to extinguish the blaze. Militia units captured twenty-seven people.[66] Heathcote was both mayor and presiding judge of the trial of the enslaved accused of violent revolt. Twenty-one were executed, including being burned alive, hanged, or broken at the wheel, and six committed suicide. On April 11, Heathcote ordered that Claus “…be broke alive upon a wheel and so to continue languishing until he be dead, and his head and quarters to be at the Queens disposal.” Robin be “hung up in chains Alive, and so continue without any sustenance until he be dead.” Quaco “be burnt with fire until he be dead and consumed…” and Sam “be hanged by the neck until he be dead.”

Afterwards, the council passed more restrictive slave codes. In February 1713, a law prohibited “slaves above the Age of fourteen years from going in the Streets of this City after Night” without a lantern or lighted candle, and “Any of her Majesties Subjects” within the city could apprehend enslaved persons they found after dark. The penalty for those convicted was to “be whipped at the public whipping Post fourty lashes save one.”[67] New York’s colonial legislature, the General Assembly, enacted more stringent slave codes. This included allowing enslavers to punish enslaved people “at discretion,” the appointment of “a common Whipper for their Slaves” in every town, and abolishing property ownership for freed people.[68]

Next: Mayoral Slave Trade

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1]Large vessels anchored about 200 feet from the docks. The Island at the Center of the World, p.103; Intra-American Slave Trade Database, Voyage 107291; Mary Donnan, Documents Illustrative of the Slave Trade, Vol. III, p.464; UK National Archives, Colonial Office, 5/1222, 119

[2]The population in 1712 was estimated at 5,840, “Population in the Colonial and Continental Periods, U.S. Census, link; Slavery in New York, Ira Berlin and Leslie M. Harris, 2005, p.62 table; The population in 1723 was 7,248, including enslaved. See note on population growth from Jill Lepore, Appendix A, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/V1WI8Y; New York City, 1664-1710: Conquest and Change has a description of buildings, neighborhoods, and demographics of the city and the collapse of the fortifications at the north end of the city by 1699. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, Burrows and Wallace, 1998, Kindle p.106-111, 118. Burgis View of New York City, 1717, Columbia University, link, and Library of Congress, link; “Old Slip and Cruger’s Wharf at New York: An Archaeological Perspective of the Colonial American Waterfront,” Paul R. Huey, Historical Archaeology, Vol. 18, No. 1 (1984), pp.15-37, JSTOR; An English merchant, Daniel Denton, wrote in 1670 that New Amsterdam was “built most of Brick and Stone, and covered with red and black Tile.” The Dutch fortifications on the north side of the city had fallen into disrepair by the late 1690’s. NYC Archives,” The Dutch & the English Part 5: The Return of the Dutch and What Became of the Wall,” link; “The Preservation and Repair of Historic Clay Tile Roofs,” Anne E. Grimmer and Paul K. Williams, Spring 1993, link; Mapping Early New York online by the New Amsterdam History Center; A Glance at New York in 1697: The Travel Diary of Dr. Benjamin Bullivant, p.63

[3] New York City, 1664-1710: Conquest and Change, Ch.2

[4] Colonial New York: A History, Michael Kammen, 1996, Chapter 7; discussed in Black and White Manhattan, Chapter 2

[5] The Island at the Center of the World, p.49 and 58; The Lenapes, Grumet, Robert, 1989, p. 38-43; Gotham: A History, p.86; Buried Beneath the City: An Archaeological History of New York, Kindle edition, Ch.1, p.83-97

[6] :New York in 1692. Letter from Charles Lodwick to Mr. Francis Lodwick and Mr. Hooker,” dated May 20, 1692 ,pp.244, HathiTrust, link

[7]Free residents were British subjects, aliens or denizens. “Naturalization in England and the American Colonies,” A. H. Carpenter, The American Historical Review, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Jan., 1904), pp. 288-303 (16 pages), https://doi.org/10.2307/1833367; De Peyster’s wealth is in New York City tax assessments from 1695 to 1699 and is ranked as the second in shipping, just below Rip Van Dam, in New York City, 1664-1710: Conquest and Change, Chapter 3: The Merchants.

[8] Donated land: Cities in the Wilderness: The First Century of Urban Life in America, 1625-1742, Carl Bridenbaugh, 1964, p.148; De Peyster’s activities as a merchant: Merchants & Empire: Trading in Colonial New York, Cathy Matson, 1998, p.60 & p.137 and New York City, 1664-1710: Conquest and Change, Chapter 3: The Merchants; Lofty buildings: A Glance at New York in 1697: The Travel Diary of Dr. Benjamin Bullivant, p.63

[9].When I Die, I Shall Return to My Own Land: The New York City Slave Revolt of 1712, Kindle edition, Ben Hughes, p.115 and p.240; Slavevoyages.org ##107291; Donnan p.464; original records at CO 5/1222_03, 119, does not state number of enslaved

[10] 1703 New York City census, East Ward, U.S. Census Bureau, link, pp.171

[11] Stevedores were enslaved: When I Die, I Shall Return to My Own Land, Kindle p.69; Enslaved owned by the Dutch West India Company built much of the infrastructure of New Amsterdam, including aiding construction of the fort, clearing land, and building roads. In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863, Leslie M. Harris, Kindle edition, p.14; Slavery in New York, online edition p.62 table; Bound by Bondage: Slavery and the Creation of a Northern Gentry, Nicole Saffold Maskiell, 2022, Kindle edition, p.3, enslaved of the Dutch West India Company worked on construction and maintenance

[12] Slavery in New York, p.4

[13] The Island at the Center of World, ch.3

[14] Bound by Bondage, Kindle, p.23-24 and 46-49

[15] “The First Arrival of Enslaved Africans in New Amsterdam,” New York History, Jap Jacobs, Summer 2023, pp. 96-11

[16] Slavery in New York, online edition, p.4, 47, 60, 64, 126, and 127; New York Historical Society, Slavery in New York, Fact Sheet

[17]“The First Arrival of Enslaved Africans in New Amsterdam.” “‘To experiment with a parcel of negros:’ Incentive, Collaboration, and Competition in New Amsterdam’s Slave Trade, Journal of Early American History, Dennis J. Maika, September 2020

[18] Slave Voyages Database, voyage #11295; New Netherland Institute voyage 170, link; “The Tale of the White Horse: The First Slave Trading Voyage to New Netherland,” Dennis J. Maika, link

[19] Slavevoyages.org, voyage ID #11414; “The Tale of the White Horse”

[20] “The Tale of the White Horse”

[21] Taking Manhattan, p.17, 64; “To experiment with a parcel of negros,” p.66

[22] Taking Manhattan, p.262-265; Sale of the captives from the Gideon on p.292 and in “‘To experiment with a parcel of negroes,'” p.66 and Books of General Entries of the Colony of New York, Vol. I, p.57

[23] Ibid, p.260

[24] Ibid., p.61,260

[25] The Records of New Amsterdam, Minutes of the court of burgomasters and schepens, Jan. 8, 1664, to May 1, 1666, p.250; New Amsterdam History Center, Mapping Early New York Encyclopedia, link

[26] New Netherlands Institute voyages database, search by owner or charterer and Voyage 108

[27] The Records of New Amsterdam, Minutes of the court of burgomasters and schepens, Jan. 8, 1664, to May 1, 1666, p.250; Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1675-1776 v.8 (1774-1776), p.149, HathiTrust, link; hereafter MCC

[28] Merchants and Empire, p.27; 60, 64, 95, 147, 189, 222; 94, 398 n.80; 53, 63, 81, 95, 147, 179, 222; 179; 28; 60, 137; 340 n. 40; 144; 221, 224; 420-21 n.16; 94; 79; 76, 222; 90; 63, 99; 222; 61, 77, 96, 151; 143; 60-61; 98, 261, 425 n.42; 63, 146, 209, 373 n.28; and151, 153, 188, 209

[29] Ulster County Archives, Dutch court records of Wiltwyck 1661-1709, April 4 1667 case and October 4 1667 case

[30] Slave named Prince: Ulster County Archives, Dutch court records of Wiltwyck 1661-1709, mortgage lists the sale price as 300 schepels of wheat; New Netherland Institute defines a schepel as 0.764 bushel wheat; 1.29 bushels salt; other slave sale: Minutes of the Court of Burgomasters and Schepens of New Amsterdam, July 12, 1663 – May 1664, “New York City, New York, United States records,” FamilySearch, viewer image 17 of 196

[31] Leonora and Leeuwinne; Trans-Atlantic Slave Voyages Database #11781

[32] Pirates, Merchants, Settlers, and Slaves: Colonial America and the Indo-Atlantic World, p.39-40

[33] List of Freight Four Ships Bound from New York to Madagascar, CO 5/1042, 98, pp.243

[34] Pirates, Merchants, Settlers, and Slaves, p.52

[35] “Letter from Giles Shelley on Illegal Trading,” Documents relating to the colonial history of the state of New Jersey, 1631-1776, Vol. II, pp.289-90, link; “The Madagascar Connection: Parliament and Piracy, 1690-1701”, P. Bradley Nutting, The American Journal of Legal History, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Jul., 1978), pp. 211-213, https://doi.org/10.2307/845181

[36] 1686 Dongan charter, pp.5, Hathi Trust, link; MCC, 1675-1776, Vol. I, p.301

[37] MCC, 1675-1776, Vol. I, p.135, 220

[38] James Duane: A Revolutionary Conservative, p.49; Minutes of the Common Council provides proceedings and the names of aldermen and mayors

[39] “New York’s Earliest Mayors,” Kenneth R. Cobb, NYC Archives, link: Historical Society of the New York Courts, Colonial New York Under British Rule, link

[40] The Municipal Revolution in America: Origins of Modern Urban Government, 1650-1825, Jon C. Teaford, 1975, p.25

[41] The Municipal Revolution in America, p.18-19

[42] The Municipal Revolution in America, p.19-20; Public Property and Private Power: The Corporation of the City of New York in American Law, 17130-1870, Hendrik Hartog, 1983, p.37-40; lists of Freemen is in Collections of the New York Historical Society for the year…, Vol. 18 (1885), Hathi Trust, link

[43] Transcript of the Duke of New York’s Laws, 1665-1675, Historical Society of the NY Courts, link

[44] MCC, 1675-1776, Vol. I, p.225-226; mentioned in Bound by Bondage, p.90

[45] “The colonial laws of New York from the year 1664 to the revolution…,” v.1 1664-1720, pp.597-98, link

[46] Root and Branch: African Americans in New York and East Jersey, 1613-1863, Graham Russell Hodges, Ch.1

[47] MCC, 1675-1776, Vol. IV p.76-79

[48] In the Shadow of Slavery, p.30

[49] Select cases of the Mayor’s court of New York City, 1674-1784, pp.742; FamilySearch

[50] In the Shadow of Slavery, Kindle edition, Chapter 1. Slavery in New York, p.62. New York Historical Society, Slavery in New York, Fact Sheet

[51] “Born to Run: The Slave Family in Early New York, 1626 to 1827,” Vivienne L. Kruger, Ph.D. dissertation, p.23; In the Shadow of Slavery, Ch.1

[52] In the Shadow of Slavery, Ch.1

[53] c.1703 census, NYC East Ward, U.S. Census Bureau, list; Inhabitants of Colonial New York, p.22

[54] “A Glance at New York in 1697: The Travel Diary of Dr. Benjamin Bullivant,” p.63; c.1703 census, NYC East Ward, U.S. Census Bureau, list; Inhabitants of Colonial New York,

[55] c.1703 census, NYC East Ward, U.S. Census Bureau, list; Inhabitants of Colonial New York, p.32

[56] Slavery in New York, p.61-62

[57] Recognizing Enslaved Africans of Larchmont Mamaroneck, List of Enslavers and Enslaved; Caleb Heathcote, Gentleman Colonist…, Dixon Ryan Fox, 1926, p.111-115 and quote from p.133

[58] New York State Archives, Gerardus Stuyvesant, probated will, 1786; Bowery Number One farm: The New Netherland Institute and The New Amsterdam History Center

[59] Robert Livingston and the Politics of Colonial New York, p.90, n.35; In letter: Rek van ship de Margriet van Madakasker naer Barbados & nae Virginia, The Gilder Lehrman Collection, GLC03107.00179

[60] Stephanus: Northeast Slavery Records Index; New York Probate Records, 1665-1699 vol 1-2, April 14, 1700, FamilySearch.com; Jacobus: In the c.1703 census, Jacobus had five enslaved people in his household in New York City. U.S. Census, Before 1790, NYC Dock Ward. While Jacobus may not have lived on his plantation, he did have enslaved people (both Africans and Native Americans) working there. Van Cortlandt House and Museum, link. The Van Cortlandt House and Museum website and probate records reveal the enslaved of Jacobus, New York, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999, Probate Date 13 Sep 1740, Ancestry.com

[61] Liberty’s Chain: Slavery, Abolition, and the Jay Family of New York, p.20 footnote 25. New York City, 1664-1710: Conquest and Change. “New York Slave Trade, 1698-1741: The Geographical Origins of a Displaced People,” Jeanne Chase, 2003, link

[62] Archival Collection Papers, 1698-1702. Van Cortlandt, Jacobus, 1658-1740? 1698 – 1702, The New York Historical Society, link to reference,

[63] New York State Archives has the original petition. It is unclear which ship she sailed on and how Governor Hunter disposed of her case. Southold town records have a notice of a sale from James Parshall to John Parker of Sarah on March 27, 1698. However, this appears to be recorded on May 10, 1712. Southold town records / copied and explanatory notes added by J. Wickham Case v.2, 1884, p.179. A 1918 history of Southampton notes the case as an example of Indian slavery at the time and includes the text of Sarah’s petition: History of the Town of Southampton, 1918, p.120. In a 1698 census, John Parker is on the list for Southampton. The list includes male Indians over 15 but “the Squas and children few of whom have any nam[e].” She does not appear in census records for New York City either. The Documentary History of the State of New-York, ed. by E.B. O’Callaghan, Vol. I, p.665 and 669; NYG&B, Pre-1750 New York lists; Calendar of historical manuscripts in the office of the secretary of state, Albany, N.Y. by New York Secretary of State, Vol. II, E.B. O’Callaghan, p.394. “Indigenous Freedom Suits, Epistemological Mobilities, and the Deep Archive,” Nancy E. van Deusen, Slavery & Abolition, pp.519-537, https://doi.org/10.1080/0144039X.2023.2236435

[64] Calendar of historical manuscripts in the office of the secretary of state, Albany, N.Y., New York Secretary of State, E.B. O’Callaghan, Vol. II, p.433; New York, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999, George Norton, Will Date 1 May 1715, Wills, Vol 008, 1710-1716, Ancestry.com

[65] In the Shadow of Slavery, p.38-40; Black and White Manhattan, Ch.4

[66] In the Shadow of Slavery, p.37; When I Die, I Shall Return to My Own Land: The New York City Slave Revolt of 1712, Ben Hughes, 2021, Kindle edition, throughout

[67] MCC, 1675-1776, Vol.III, p.28-31, link

[68] The colonial laws of New York from the year 1664 to the revolution…, v.1 1664-1720, pp.761-767; the whipper was also in a 1702 slave code, pp.520; When I Die, I Shall Return to My Own Land, throughout; Caleb Heathcote, Gentleman Colonist…, Dixon Ryan Fox, 1926, p.111-115: In the Shadow of Slavery, p.33; Black and White Manhattan, Ch. 3; “Slave Codes,” Replication data for: New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan, link

Copyright 2025 Paul Hortenstine