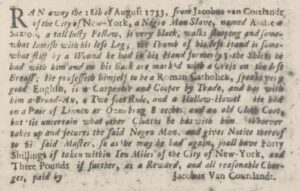

Runaway notice for Andrew Saxon, New York Gazette, October 1, 1733, NYPL

Jacobus Van Cortlandt, Mayor 1710-1711 and 1719-1720: Van Cortlandt (1658–1739) was a merchant who sold enslaved persons on consignment. He ran the family shipping business from the Caribbean and when he returned to New York City he continued to work in trade, brewing, farming, and milling. He sold flour, bread, bacon, and butter to Curacao and Jamaica, which is in his account book from 1699-1702. He sold the enslaved who arrived from the West Indies on consignment in New York City and the surrounding countryside.[1]

Van Cortlandt had enslaved people who did domestic chores, grew wheat, maintained roads, built barns, and operated two mills on his plantation, which is today’s Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx.[2] He also sold enslaved people to nearby farmers.[3] Through his daughter Mary, he was the grandfather of Dr. James Jay (1732–1815) and John Jay (1745–1829).

Between 1698 and 1701, he sold enslaved people on consignment who were carried on ships from Antigua, Jamaica, Barbados, St. Christopher, Curaçao, Campeche, and Madeira.[4] Many of his letters in 1698 disclose the effect on the prices of enslaved persons after the arrival of ships from Madagascar owned by Frederick Philipse.

- On April 15, 1698, Van Cortlandt wrote to Miles Mayhew that he received “one negro woman” on consignment from him but there was a “dull markett by reasons of three vessels coming in river with slaves – two from Madagascar and one from Gieny [Africa]…”[5] He wrote to another merchant the same day about “one negro” he received and the same complaint about the dull market.

- On May 16, 1698, he wrote Mayhew about a female slave he was unable to sell: “I have been very often in despair of Ever selling the woman for our Country-people do no Care to buy old slaves; therefore would advise you or any of your fiends to Send no Slaves to this place that exceed 25 Years of age.” In a letter to Barnabas Jenkins, he warned that a male slave with “distemper about his throat” would be unlikely be purchased.[6]

- On May 20, 1698, he wrote to John Roe that he received money and “the negro man” sent on the sloop Dolphin, and the slave would be sold “for £40 to be paid in a month.”[7] He records other goods: logwood, rum, molasses, sugar, indigo, cotton, and pimento.

- On June 4, 1698, he wrote to Mayhew and another merchant that large number of enslaved people from the three ships still “makes the slaves to sell very slow.”[8] He also notes molasses, rum, indigo, and cotton in the shipment.

- On June 23, 1698, he wrote to Mayhew that he had sold two enslaved people belonging to Samuel Phillips, Jacob for £41 and the other for £38.[9]

- On June 30, he wrote to Barnabas Jenkins he sold two enslaved persons that belonged to Madame Waterhouse.[10] He wrote to Jenkins again on July 16 that he received a slave that belonged to Charles Fuller but feared he would not sell due to “the distemper about his throat.”[11]

- On August 18, 1698, he complained to a West Indies agent that “The Negro Mingo as yet not sold shall be forced at last to sell him at a low price because of his age besides the great quantity of slaves that are come to this place this year.”[12]

Frederick Philipse, a slave trader and likely the richest man in New York City, gave his grandson Frederick Philipse the bulk of his estate when he died in 1702, including his enslaved persons. He left Jacobus Van Cortlandt and his wife Eva de Vries (his adopted daughter) the house in New York City they lived in.[13]

- In the c.1703 census, Van Cortlandt had five enslaved persons in his household in New York City.[14]

- Van Cortlandt probably did not have live on his plantation. He had enslaved people (both Black and Indigenous persons) laboring there growing wheat, making improvements to the land, building barns, two mills, and building a dam that turned Tibbett’s Brook into a lake.[15]

- A runaway notice from October 1, 1733, by Jacobus Van Cortlandt in the New York Gazette:

Ran away the 18th of August 1733, from Jacobus van Cortlandt of the City of New York, a Negro Man Slave, named Andrew Saxton, a tall lusty Fellow, is very black, walks slooping and somewhat lamish with his left Leg; the Thumb of his left hand is somewhat still by a Wound he had in his Hand formerly; the shirts he had with him and on his Back are mark’d with a Cross on the left Breast; He professeth himself to be a Roman Catholick, speaks very good English, is a Carpenter and Cooper by Trade, and has with him a Broad-Ax, a Two-foot Rule, and a Hollow-Howel. He had on a Pair of Linnen or Oznabrug Breeches, and an old Cloth coat, but ‘tis uncertain what other Cloughs he has with him. Whoever takes up and secures the Said Negro Man, and gives Notice thereof to his Said Master, So as he may be had again, shall have Forty Shillings if taken within Ten Miles of the City of New York, and Three Pounds if further, as a Reward, and all reasonable Charges, paid by Jacobus Van Cortlandt.[16]

Probate records show that in his will, Jacobus named these enslaved people as his property:

- Pompey, identified as “my Indian man slave;” Piero “my negro man slave;” John “my negro man slave;” Frank “my negro man slave;” Hester a “negro woman;” and Hannah a “negro woman.”

- Also unnamed, uncounted children, identified as the existing children of Hannah “Together with all their children that already are or hereafter shall be born of the body of the said negro woman Hester (except such of the said children as I may think fit in my lifetime to dispose of by deed of gift or otherwise).”[17]

His children included:

- Frederick Van Cortlandt (1699–1749), who married Francina Jay, daughter of Auguste Jay and Anne Marika Bayard. Frederick built the Van Cortlandt House in 1748.

- Mary Van Cortlandt, who in 1728 married Peter Jay (b. 1704), the brother of Francina Jay.

- Margaret Van Cortlandt, who married Abraham De Peyster Jr., son of Mayor De Peyster.

In May 2018, the New York Times published a story on questions over current ownership of a graveyard of enslaved people on the Van Cortlandt property. In the article, the historian of the Van Cortlandt House Museum stated that Frederick Van Cortlandt and Augustus (his son) owned twenty-six enslaved people. In a circa 1790 census, Frederick is listed as owning nine enslaved people.[18] Frederick also owned a slave ship, the brigantine Dolphin.[19]

Van Cortlandt House Museum is part of a 1,000-acre urban park that encompasses what was once the Van Cortlandt family’s plantation. From its website:

When Frederick van Cortlandt had this house built in 1748-1749, it was part of Yonkers in Westchester County. Frederick van Cortlandt’s father, Jacobus, a wealthy merchant, first purchased land in this vicinity in 1693. Over the years, the Van Cortlandts continued purchasing lots from local farmers until they amassed a large estate stretching well beyond the boundaries of modern Van Cortlandt Park. In 1701, Jacobus van Cortlandt paid local Munsee Lenape people to secure legal ownership of the land, which the Van Cortlandts referred to as their “Yonkers plantation.” In the colonial period, Van Cortlandt Park’s modern day athletic fields were filled with acres of wheat, buckwheat, rye, and corn in addition to farm animals.

Three generations of the Van Cortlandt family held enslaved Africans on the property from 1698 until 1823. Some, such as Dinah, worked as house servants. Others, like Piero the miller and Levellie the boatman, performed skilled labor that increased the profitability of the plantation. Enslaved Africans held by the Van Cortlandts left a legacy in today’s Van Cortlandt Park that is still visible.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Jacobus Van Cortlandt Shipments Book, NYHS v20 n04, Quarterly Bulletin, October 1936, link, “Archaeological Excavations at Van Cortlandt Park,” The Bronx, 1990-1992, link; Black and White Manhattan, Chapter 2; Liberty’s Chain, p.20 footnote 25

[2] Stephanus: Northeast Slavery Records Index; New York Probate Records, 1665-1699 vol 1-2, April 14, 1700, FamilySearch.com; Jacobus: In the c.1703 census, Jacobus had five slaves in his household in New York City. U.S. Census, Before 1790, NYC Dock Ward. While Jacobus may not have lived on his plantation, he did have enslaved people (both Africans and Native Americans) working there. Van Cortlandt House and Museum, link. The Van Cortlandt House and Museum website and probate records reveal the slaves of Jacobus, New York, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999, Probate Date 13 Sep 1740, Ancestry.com

[3] Liberty’s Chain: Slavery, Abolition, and the Jay Family of New York, p.20 footnote 25. New York City, 1664-1710: Conquest and Change. “New York Slave Trade, 1698-1741: The Geographical Origins of a Displaced People,” Jeanne Chase, 2003, link

[4] “New York Slave Trade, 1698-1741: The Geographical Origins of a Displaced People,” Jeanne Chase, 2003, link

[5] Archival Collection Papers, 1698-1702. Van Cortlandt, Jacobus, 1658-1740? 1698 – 1702, The New York Historical, digital p.4

[6] Black and White Manhattan, Chapter 2

[7] Archival Collection Papers, 1698-1702. Van Cortlandt, Jacobus, 1658-1740? 1698 – 1702, The New York Historical, digital p.11

[8] Archival Collection Papers, 1698-1702. Van Cortlandt, Jacobus, 1658-1740? 1698 – 1702, The New York Historical, digital p.12-13

[9] Archival Collection Papers, 1698-1702. Van Cortlandt, Jacobus, 1658-1740? 1698 – 1702, The New York Historical, digital p.18

[10] Archival Collection Papers, 1698-1702. Van Cortlandt, Jacobus, 1658-1740? 1698 – 1702, The New York Historical, digital p.19

[11] Ibid., digital p.24

[12] The New York African Burial Ground: Unearthing the African Presence in colonial New York, Vol. III, GSA, report

[13] Abstracts of wills on file in the Surrogate’s Office, City of New York, 1665-1801. V. 1, Page viewer p.378, Will dated October 26, 1700, FamilySearch, link

[14] U.S. Census, Before 1790, NYC Dock Ward

[15] Van Cortlandt House and Museum, link

[16] Pretends to be Free: Runaway Slave Advertisements from Colonial and Revolutionary New York and New Jersey. New York: Taylor and Francis, 1994, p.9

[17] New York, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999, Probate Date 13 Sep 1740, Ancestry.com

[18] Northeast Slavery Records Index, citing Van Cortlandt House Museum website

[19] Intra-American Slave Voyage Database #107779; Donnan p.495; and #107793, Donnan p.496

Copyright 2025 Paul Hortenstine