by Ned Benton

How did John Cox and Andrew Cole escape from slavery in Mamaroneck Township during the 1770s and end up on Nova Scotia? The story of these two men, whose connection to Mamaroneck had been lost for more than 200 years, was originally traced through documents compiled for the Slavery in Mamaroneck Township project.

Census records affirm that slavery was common in Mamaroneck before 1827, when slavery was abolished in New York State. Those records and other documents have revealed details of local slaveholders and slaves, which are presented, in the Slavery in Mamaroneck Township project, in a table of The Slaveholders and The Slaves (updated in December, 2016). Further description of the documents behind the list are given in Slavery in Mamaroneck: Remembering Bet, Phelby, Candice, Jack, Hannibal, Telemaque…

John Cox and Andrew Cole

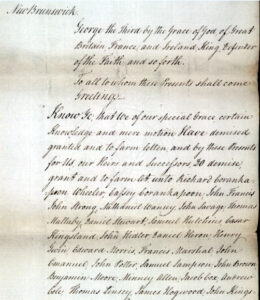

The two slaves appear in the Book of Negroes, a hand-written list of Black passengers allowed to leave New York for Nova Scotia in 1783 because of their service to the British during the Revolutionary War. Two entries for a ship named the Clinton read as follows:

The two slaves appear in the Book of Negroes, a hand-written list of Black passengers allowed to leave New York for Nova Scotia in 1783 because of their service to the British during the Revolutionary War. Two entries for a ship named the Clinton read as follows:

- John Cox, 31, stout fellow. Formerly the property of Eleazer Goddin, Maroneck (sic), New York; left him 7 years ago.

- Andrew Cole, 26, stout fellow. Formerly the property of Ben Cole, Marroneck (sic), New York; left him 4 years ago.

What do we know about John Cox and Andrew Cole? To understand how they came to be slaves and what might have happened when they moved to Nova Scotia, we need to begin with the story of how slavery came to Westchester County.

Slavery in Westchester County

The Dutch West India Company had introduced the slave trade to the New York area in 1626, and it had spread north to places like the Philipsburg Manor. According to historian Edgar McManus, author of A History of Negro Slavery in New York, in the mid 1600s, there was such an acute shortage of agricultural labor in the Hudson Valley that planters advertised to buy “any suitable blacks available.”

As early as 1698, slavery is officially documented in Mamaroneck Township. Captain James Mott, William Palmer and Ann Richbell are all recorded as slaveholders. (See Census of Mamaroneck, Westchester Co. New York, 1698.)

New Rochelle, Mamaroneck and Rye from a 1781 Chart titled “Position du camp de l’armée combinée a Philipsburg du 6 juillet au 19 aoust.” (Library of Congress American Memory Project)

By 1750, there were 11,014 slaves in the Colony of New York — almost one out of every six persons – residing here in Mamaroneck Township. (See: Establishing Slavery In Colonial New York.)

Why Did John Cox and Andrew Cole Escape and Join the Brits?

Mamaroneck’s slaves included John Cox, born in about 1752 and owned by Eleazer Goddin, and Andrew Cole, born in about 1757 and owned by Ben Cole. Ben Cole may have been a relative of James Coles, the Mamaroneck cobbler (See Judith Spikes, Larchmont NY: People and Places, 1991, p.13) or Joseph or John Coles, who appeared in the 1790 Mamaroneck census.

In 1775, The Earl of Dunmore who was the British Governor of Virginia, issued a proclamation urging slaves to join arms with the British: “I do hereby further declare all indented Servants, Negroes, or others, (appertaining to Rebels,) free that are able and willing to bear Arms, they joining His MAJESTY’S Troops as soon as may be, foe the more speedily reducing this Colony to a proper Sense of their Duty, to His MAJESTY’S Crown and Dignity.”

In reply, the General Convention of the Dominion and Colony of Virginia threatened dire consequences: “WHEREAS lord Dunmore, by his proclamation, dated on board the ship William, off Norfolk, the 7th day of November 1775, hath offered freedom to such able-bodied slaves as are willing to join him, and take up arms, against the good people of this colony, giving thereby encouragement to a general insurrection, which may induce a necessity of inflicting the severest punishments upon those unhappy people, already deluded by his base and insidious arts; and whereas, by an act of the General Assembly now in force in this colony, it is enacted, that all negro or other slaves, conspiring to rebel or make insurrection, shall suffer death, and be excluded all benefit of clergy.”

The Phillipsburg Proclamation Invites Cox and Cole to Join Up

In 1779, the British Commander of New York issued the Phillpsburg Proclamation, which extended the same offer to slaves in New York, even those who escaped from their masters.

In 1776, John Cox escaped from Eleazer Goddin. It is hard to say whether he was motivated by the 1775 Dunmore Proclamation. But, Andrew Cole made his escape in 1779 – the same year as the Phillipsburg Proclamation, so it’s a good guess that he heard the call and responded.

Following the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War in 1783, the British forces gathered in New York to be evacuated. Congress instructed General George Washington to claim all confiscated property from the British, including slaves. However, the British commander-in-chief, Sir Guy Carleton, refused to comply with General Washington’s demand that the slaves be returned to their owners. Sir Carleton and General Washington agreed that the slaves would be permitted to emigrate and that the British would compensate their owners.

John Cox and Andrew Cole were among the 3,000 Black Loyalists who were issued certificates of freedom and permitted to emigrate to Canada by ship. Their ship, the Clinton, was bound for Annapolis, Nova Scotia. However, there was no record of Cole or Cox in the registers of Black Loyalists in the two major settlements: Birchtown or Annapolis.

The Rest of the Story…

The story of slavery in America is told in thousands of documents – legal records, personal letters, government registers, business transactions and public reports. But the story of individual slaves or slaveholders is told when the connections are made – when a name can be traced over places and times to reveal more complete evidence of a life.

Making more of those connections is becoming possible now that historians in the United States, Canada, England and Africa are finding, assembling and digitizing records relating to slavery in America. In the years to come, the aim of the Slavery in Mamaroneck Township project is to make use of the newly available documents to weave together stories of the slaves who lived in our community.

The Black Loyalist Heritage Society in Shelburne, Nova Scotia, did not have any records of either Cox or Cole disembarking or living in the Annapolis area. However, recently, they put us in touch with Stephen Davidson, a teacher, novelist and historian who lives near Halifax and was able to identify several documents that reveal what happened next.

Andrew “Coal” in St. John’s

Davidson reported that Andrew Cole is identified on a list of Black Loyalists compiled by David Bell for his book, The Early Loyalists of Saint John (in Appendix VIII, pp. 172-255). His name appears as Andrew COAL, and he is listed as having a wife. Davidson further explained: “In 1783, St. John’s meant the mouth of the St. John River in what is now New Brunswick (but was then the north-western part of the colony of Nova Scotia). Loyalists flooded into Parrtown by the thousands, and within two years the tiny settlement at the mouth of the St. John River became the city of Saint John.”

Joining Up with Corankapone

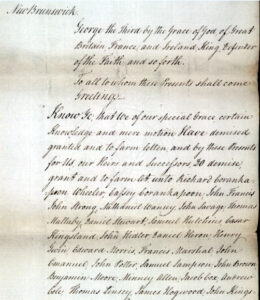

The next set of documents involve a land grant [1] based on a

The next set of documents involve a land grant [1] based on a  petition [2] by another freed slave, Richard Corankapone Wheeler, which was signed for “Jacob Cox” and “Andrew Cole” and others. Davidson explains that Cole was therefore “part of a community of Black Loyalists that began to form as the refugees sailed for British North America. The men were from many colonies, but they acted together, placing themselves under the leadership of Richard Wheeler (Corankapone), another Clinton passenger.”

petition [2] by another freed slave, Richard Corankapone Wheeler, which was signed for “Jacob Cox” and “Andrew Cole” and others. Davidson explains that Cole was therefore “part of a community of Black Loyalists that began to form as the refugees sailed for British North America. The men were from many colonies, but they acted together, placing themselves under the leadership of Richard Wheeler (Corankapone), another Clinton passenger.”

In A Most Determined Man, Davidson describes Corankapone: “The former Richard Wheeler was a healthy 30 year-old bachelor who had bought his freedom in 1776 from Caleb Wheeler, his master in New Jersey. Although over 210 black loyalists sailed with Corankapone, fifteen of them were to become close friends in the new colony of New Brunswick and would look to him as their leader. Their surnames included Holland, Cole, Sampson, VanRyper, Francis and Stewart. They had once been enslaved in Virginia, Pennsylvania, New York, and South Carolina as well as New Jersey. In 1783, they thought they were about to embrace the life of free men as they settled alongside white loyalists at the mouth of the St. John River.”

Is Jacob Cox the Same Person As John Cox?

The Corankapone documents refer to “Jacob Cox” while the Mamaroneck slave was known as “John Cox.” Are they the same person? We don’t know for sure, but there are good reasons to believe they are:

- Jacob Cox is a signer, with Andrew Cole, of two Corankapone petitions. How likely is it that John Cox disappears and Jacob Cox simultaneously materializes as Andrew Cole’s partner in two petitions representing that they are freed slaves?

- The freed slaves on Corankapone’s petition were people who joined with him on the Clinton. There was no “Jacob Cox” on the Clinton, so there is no evidence that Jacob was a different person than John.

- In fact there was no “Jacob Cox” in the entire Book of Negroes which identified all of the former slaves freed by the British.

- Cox’s and Cole’s names appear adjacent in the Book of Negroes and in the petitions.

- In Professor Bell’s census of Saint John in 1783 and 1784, he lists a “Jacob Cox” but not a “John Cox.” Once again there is no evidence of a different “John Cox” in the area.

- There is no evidence that Cox or Cole disembarked in Annapolis. [2]

Did They have Wives and Families?

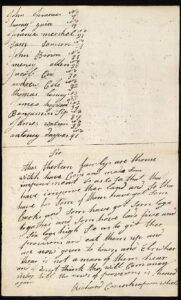

Professor Bell’s inventory shows Andrew Cole as being married as of 1784, and Jacob Cox as having a “child under 10,” a category which included anyone from infancy through age 9. How do we explain their families?

A review of the ship manifest for the Clinton suggests a possible answer. Passengers on the Clinton (listed on the same page of the manifest) included Mary Coles, Nelly Cox, and two children of Nelly Cox. On the manifest, Mary Coles was identified as free-born from Mosquito Cove in Long Island, a place now know as Glen Cove. Nelly Cox was listed as the former property of Paul Burtis in Long Island, although the ownership of her two children is not clear. Cox and Cole may have met these women during the war, or they may have met immediately before or during the trip from New York to New Brunswick. While our evidence is incomplete, I believe that the best interpretation of the evidence is that both men were married, since:

- The male and female Coxes and Coles are on the same ship with the same destination.

- Both Cox and Cole lived as married men soon after their arrival in Saint John.

- It is relatively unlikely that the two women were on the ship in any other capacity than as the wives of male passengers. To qualify for passage, the refugee had to have been recorded as being in service to the British. A women might have served as a seamstress, cook, laundress, and even as a spy, but the more likely scenario is that they were on board as wives. A woman could not qualify for passage on the Clinton simply as a personal preference. The orders authorizing the emigration clearly stated: “The Refugees and all Masters of Negroes will be attentive that no Negro is permitted to embark as a Refugee who has not recorded himself within the British Lines.” If Nelly Cox and Mary Coles were not the wives of Cox and Cole, what was their status on the Clinton?

- There are notable cases of Black Loyalist slaves marrying and fathering children while in British military service. [3]

So we know that Andrew Cole arrived in St. John. There is reasonable but imperfect evidence that John Cox also arrived, and is the Jacob Cox in subsequent records. The records show that Cox and Cole were both married, and that Cox, in Saint John, also had a child.

What Happened in Saint John?

Stephen Davidson’s essay A Most Determined Man, describes the horrendous conditions which Corankapone and his friends Cox and Cole and their families faced. Blacks were not permitted occupations beyond being servants or laborers and were not even allowed to fish.

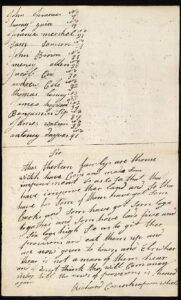

Davidson reports: “By January 1785, their situation had become unbearable. Thirty-four black loyalists, including his 15 shipmates, asked Corankapone to be their “captain” and petition the government for land outside the city. Corankapone’s petition reviewed their situation: That the Authority at Carleton were pleased to set apart Small Lots … upon which they have Built and now reside – That they find by Experience that they, their Wifes and Children cannot subsist … and are under Apprehensions of Suffering this Winter, Labour and Provisions being so very Scarce … That Your Petitioner hopes that those that knew him think he sincerely desires that the Blacks, should lead Industrious, honest Lives and instead of being a Burthen, should be an Advantage to the Community … Your Excellency’s Petitioner therefore most humbly Prays a Grant may be made to the Blacks named in the annexed List of the Land … or such Relief in their Wretched Circumstances. “

Cox and Cole were among the petitioners, and in 1787 the land grands were issued. However the conditions continued to be terrible, and eventually Corankapone became aware of a project to resettle black loyalist refugees to Sierra Leone. In A Most Determined Man, Stephen Davidson describes how Corankapone, upon learning about the Sierra Leone option, walked the 400 miles to Halifax to accept the offer of resettlement in Africa. In A Loyalist Constable in Africa, Stephen Davidson recounts Corankapone’s life in Freetown, Sierra Leone.

For Andrew Cole, the documentary trail now goes cold. However, when Corankapone walked to Halifax, four of his closest friends walked with him and departed in January 1792 for Sierra Leone. Was Andrew Cole one of the four friends? Perhaps, as the records of life in Freetown are reconstructed and digitized, the name of Andrew Cole will once again emerge.

As to Jacob (or it it John?) Cox, Stephen Davidson reports the following: “It is interesting that I couldn’t find any other Coxes in this period of New Brunswick’s history other than Jacob Cox. It seems to have been a rare name. The next Cox that I found was a Jeremy Cox who married in a community along the St. John River in 1806. If this were Jacob Cox’s “child under ten” in 1783, he would certainly be of marriageable age by 1806. If we follow this line of speculation a little further, perhaps Jacob Cox (the true John Cox?) stayed on the land he received while his Clinton friends left for Sierra Leone in 1791. His son Jeremy Cox then married in the riverside community of Gagetown in 1806.”

Sierra Leone Company Ad

So, if we adopt the most likely – if not absolutely certain – interpretations of the records available, this is the story: Cox and Cole, having escaped from their Mamaroneck slave-holders to fight with the British in the Revolutionary War, embark on the Clinton in 1783 bound for Nova Scotia with their wives and, in Cox’s case, two children. They disembark in Saint John and set out to make new lives for themselves and their families. Facing many hardships, including racist restrictions on their new-found freedom, they take different paths. Cole emigrates to Sierra Leone where he is promised greater freedom and land. Cox stays on, and perhaps it is his son Jeremy who survives to be married in 1806.

Is this what really happened? It is the most likely interpretation of the documents available at this point. But we will be continuing to search for further clues to solve the mysteries of what happened to Mamaroneck’s former slaves.

References

1. Draft of a Grant made to Wheeler and Company, 1787, Fredericton, “Black Loyalists in New Brunswick, 1783-1854,” Atlantic Canada Virtual Archives, digital image, document no. Wheeler_Richard_1785_08, p. 1. RS 108: Index to Land Petitions: Original Series, 1783-1918, , is available at Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, Fredericton, New Brunswick.

2. Stephen Davidson advises, by personal communication: “There was nothing on Cox or Cole in the 1784 Muster Roll for Annapolis County, indicating the two men did not get off the Clinton in Annapolis Royal and then later cross the Bay of Fundy to Saint John. Neither man is found in the early probate records of New Brunswick (which happen to contain details on the property of a number of Black Loyalists). The petition of Thomas Peters (a Black Loyalist who appealed to the New Brunswick government in 1791 before sailing to Sierra Leone) does not have either a Cole or Cox among its petitioners. Baptismal records for the Prince William Anglican Church in NB does not contain their names.”

3. See Thomas Peters. “Peters rose to the rank of sergeant in the regiment and he was twice wounded in battle. During this time Thomas was married to Sally Peters, a slave from South Carolina and he had a son called John (born in 1781) and a daughter Clairy (born in 1771).”

4. This article was published originally with the Larchmont Historical Society, January 17, 2011.

The two slaves appear in the

The two slaves appear in the

The next set of documents involve a land grant [1] based on a

The next set of documents involve a land grant [1] based on a  petition [2] by another freed slave, Richard Corankapone Wheeler, which was signed for “Jacob Cox” and “Andrew Cole” and others. Davidson explains that Cole was therefore “part of a community of Black Loyalists that began to form as the refugees sailed for British North America. The men were from many colonies, but they acted together, placing themselves under the leadership of Richard Wheeler (Corankapone), another Clinton passenger.”

petition [2] by another freed slave, Richard Corankapone Wheeler, which was signed for “Jacob Cox” and “Andrew Cole” and others. Davidson explains that Cole was therefore “part of a community of Black Loyalists that began to form as the refugees sailed for British North America. The men were from many colonies, but they acted together, placing themselves under the leadership of Richard Wheeler (Corankapone), another Clinton passenger.”