By Ned Benton and Judy-Lynne Peters

It might come as a shock to those in the field of public administration to learn that American officials – not just private individuals or businesses – played important roles in the administration of slavery. It might be a further shock to learn that slavery – and the public administration of slavery – was pervasive in the Northeast – not just the South. Data from the Northeast Slavery Records Index, an online repository of information on slavery, show the extent of slavery in Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island and Vermont, the states corresponding to ASPA District 1. Further, the NESRI documents show that public officials performed core functions required to facilitate and perpetuate enslavement, while in other cases, public administrators opposed or hindered enslavement. Even further, the NESRI database produces customized reports that show the extent of slavery in particular jurisdictions, states, counties, or cities – including those that today are home to 54 graduate public administration programs.

Based on the NESRI data, this paper outlines the governmental roles in the administration of slavery and details three examples of this involvement. It also includes links to the customized reports for localities with graduate public administration programs.

Armed with this and additional information from the NESRI database, public administration faculty can help confront the old myths about American slavery. They can educate students, colleagues, administrators, and general members of the public about slavery in their surrounding community – and in some cases – slavery in their own institutions. At the same time, using examples from the database, they can dispel the misimpression that public administration is a value neutral profession focused merely on technical competence in public service.

Public Administration of Slavery

Governments and government employees were involved in slavery through three basic functions: documentation, finance and enforcement.

Documentation: The most pervasive governmental involvement in enslavement was through colonial and post-colonial censuses, administered by public employees. The census counted both enslavers and enslaved people (sometimes as fractional individuals) in determining a jurisdiction’s official population. The official reporting legitimized slavery as a common practice. Official documentation was also an essential aspect of gradual emancipation laws that perpetuated enslavement while assuring the eventual freedom of children born to enslaved mothers, but only after decades of servitude. The laws required such births to be recorded by county, town, and city clerks, thus reinforcing both the original enslavement and the long-term servitude of the children.

Finance: Governments indirectly financed enslavement or its consequences. The gradual emancipation law in New York, for example, permitted enslavers to officially abandon children born to their enslaved mothers, resulting in placement of the children in foster care paid for by the public “Overseers of the Poor” as children of paupers. The rationale was that enslavers should not be required to support the cost of raising enslaved children who could not be sold and whose prime years of enslaved service were confiscated under the law. Another example is from the post-Revolutionary War provision in the Treaty of Paris that compensated enslavers whose enslaved people escaped to join the British forces and were subsequently freed by the British and given passage to Canada.

Enforcement: National, state and local governments incurred costs and deployed staff to capture and return enslaved fugitives to their enslavers. Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution provided that “No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.” Thus, state and local governments were required to enforce slavery from other states, even if the state had abolished slavery within its own boundaries.

CASE EXAMPLES

The following are four examples of public agencies and administrators engaged with slavery. Some acted in support of enslavement while others promoted abolition and freedom. In others, the public administrator both advanced the institution of enslavement and supported its gradual abolishment.

Joseph Whipple, Portsmouth NH Collector of Customs, Defies President Washington

Joseph Whipple made a decision that could serve as a classic case for any course on ethics and public administration dealing with the reconciliation of bureaucratic duties, personal morality, and evolving standards of justice and the common good. The case begins with Ona Judge, enslaved in Virginia as Martha Washington’s personal attendant. In 1789, President George Washington brought Ona Judge and other enslaved people from his Virginia plantation to New York to serve in the Presidential household. Then in 1790, Ona Judge went with the President to Philadelphia, after Congress moved the temporary capital there.

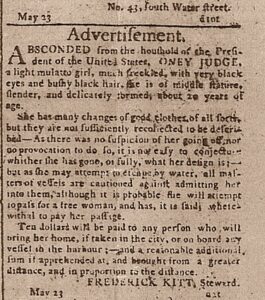

Fugitive Ad for Ona Judge, absconder from the household of the President.

Slavery had been legal in New York, but Pennsylvania had passed an emancipation act. In response, President Washington started to rotate enslaved staff back to Virginia at 6-month intervals, making their stay in Pennsylvania temporary and disabling their ability to apply for freedom in Pennsylvania. Aided by freed black people in Philadelphia, Ona Judge escaped by ship to Portsmouth, New Hampshire. After several months of freedom there, she was recognized by the daughter of U.S. Senator John Langston, who informed President Washington.

At the President’s instruction, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Oliver Walcott ordered Joseph Whipple, in his capacity as the Portsmouth Collector of Customs, to interview Ona Judge and, subsequently, arrange for her shipment back to Virginia. Whipple conducted the interview but reported that while her transport might be legally warranted, he could not carry out her involuntary shipment without public outcry and protest. He wrote “I shall be happy to facilitate the business to the utmost of my power in obedience to the pleasure of the President, it is with great regret that I give up the prospect of executing the business in the favourable manner that I had at first flattered myself it would be done.”

President Washington replied directly to Whipple with an angry letter. “I regret that the attempt you made to restore the Girl (Oney Judge as she called herself while with us, and who, without the least provocation absconded from her Mistress) should have been attended with so little Success.” Insisting that he try harder, Washington advised “The less is said before hand, and the more celerity is used in the act of Shipping her, when an opportunity presents, the better chance Mrs. Washington (who is desirous of receiving her again) will have to be gratified.”

Through inaction and non-response, Whipple prevailed over the President. Two years later Washington encouraged his nephew to travel to Portsmouth to discreetly kidnap Ona Judge. But Senator Langston who, apparently regretting his tip-off to Washington in 1796, this time tipped off Ona Judge, who eluded capture. Thanks to Joseph Whipple, Ona Judge married, had three children, and remained free in New Hampshire until she died in 1848.

Administering and Financing the Abandonment of Enslaved Newborn Children

New York’s 1799 Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery provided that “any child born of a slave within this state after the fourth day of July next shall be deemed and adjudged to be born free: Provided nevertheless. That such child shall be the servant of the legal proprietor of his or her mother until such servant, if a male, shall arrive at the age of twenty-eight years, and if a female, at the age of twenty-five years.”

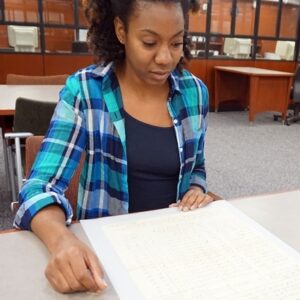

Valencia McMillan, an MPA graduate student in Forensic Accounting, examines a 200-year old invoice for the care of enslaved children, in the records of the Comptroller’s Office at the NY State Archive.

It further provided that “every person being an inhabitant of this state who shall be entitled to the service of a child born after the fourth day of July as aforesaid, shall, within nine months after the birth of such child, cause to be delivered to the clerk of the city or town whereof such person shall be an inhabitant, a certificate in writing containing the name and addition of such master or mistress, and the name, age and sex of every child so born…”

It also provided for the abandonment of the newborn children: “The person entitled to such service may, nevertheless, within one year after the birth of such child, elect to abandon his or her right to such service, by a notification of the same from under his or her hand, and lodged with the clerk of the town or city where the owner of the mother of any such child may reside; in which case every child abandoned as aforesaid shall be considered as paupers of the respective town or city where the proprietor or owner of the mother of such child may reside at the time of its birth; and liable to be bound out by the overseers of the poor on the same terms and conditions that the children of paupers were subject to before the passing of this act.”

NESRI includes documentation of the birth registries for New York and other states; the records are tagged “REG” for registrations, identifying children claimed for servitude. Alternatively, the records are tagged “ABN” to indicate the enslaver separated the child from the mother and abandoned the child to the Overseers of the Poor. In New York, the state paid $3.50 per month for the care of the abandoned children.

A compilation of these records is available at Comptroller Abandonment Invoices. They provide a clear example of “public administration of slavery,” as they show local officials invoicing state officials for reimbursements of abandonment payments made by local Overseers of the Poor.

This was not a rare activity on the part of the public administrators. Between 1799 and 1804, in a sample of ten towns, 37% of newborn children were abandoned. (See Vivienne L. Kruger, Born to Run, 1985, Chapter 13) Comptroller reports revealed that for 1803, 1804, and 1805, New York State expended 5%, 6.1% and 5.6% of the entire state budget on payments for abandoned enslaved children. Finding this to be unsustainable, in 1804, the legislature reduced the amount and duration of future state-funded payments, leaving it to towns and cities to figure out how and whether to pay for the continuation of the abandonment option. New Jersey experienced more serious problems: in 1808, 40% of the primary state budget went for these payments.

Town Clerk Gilbert Budd Approves His Own Registrations

Gradual emancipation laws and other laws required that enslavement documents be recorded in government offices. Such requirements benefited enslaved people because they usually were not parties to contracts or documents in which they were the subject. They also usually lacked secure places to store documents, and may not have been able to read them. However, it was usually the clerk’s responsibility to write out the document or specify the required language, check that the document included necessary information, be properly witnessed, be retained for future review. In Mamaroneck NY, Gilbert Budd was, according to our indexed records, the enslaver of the most people, in 1790 reporting 12 slaves in the census. He was also the Town Clerk from 1771-1776 and 1783-1807.

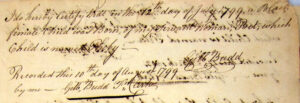

Gilbert Budd registers Bet’s child Pheby born July 12, 1799.

On August 10, 1799, Budd reported the birth of Pheby to her mother Bet, and he reported that she was born on July 12, 1799. This was the first birth registration following the effective date of the Gradual Emancipation law. If Pheby had been born on Judy 3rd, when would have been under the law a slave for life. While Gilbert Budd did not take evil advantage of the lack of fact-checking and witnesses, one might wonder how many other slips of the pen might have gone unnoticed in other jurisdictions.

It is notable that Budd appears in the document both as the enslaver registering the birth, and as the Town Clerk, recording the attestation. Recording his own attestations was apparently not illegal. Stephen Lush, the Albany Clerk did the same. (See Albany Manumissions and Registrations, p. 57)

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 Rewards Federal Commissioners

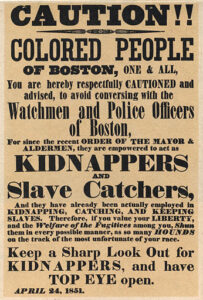

Poster in Boston in 1850 warning of kidnappers and slave catchers

Before passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, enslavers and their privately-paid agents were responsible for the recapture and transport of fugitive enslaved people. The new law designated “Commissioners” to issue warrants to slave owners, slave catchers, or U.S. marshals to capture and arrest suspected fugitive slaves. The law required that “all good citizens are hereby commanded to aid and assist in the prompt and efficient execution of this law.” Any person who interfered with an arrest, attempted a rescue, or aided or hid a fugitive slave was liable for a $1,000 fine and up to six months in jail. U.S. marshals could hire people to assist in capture and transportation. The Commissioners, appointed by federal judges to adjudicate these cases were paid by the case: $5 if the alleged fugitive was freed, and $10 if a certificate of transport was issued.

As illustrated in the adjacent poster, pursuant to the 1850 law, Boston’s Mayor empowered public employees to capture fugitives from slavery, who would be brought before federally-paid commissioners to determine their fate. This was another case in which public administrators were involved in the support of the institution of slavery.

NESRI: ACCESS TO THE ENSLAVEMENT RECORDS IN THE NORTHEAST

While the above examples show details of enslavement, the NESRI database includes a wide variety of documents that illustrate the extent and nature of enslavement throughout the region. Further, the database enables compilations of records for specific states, counties, cities or towns. These are particularly useful for current residents of these areas seeking to understand historical slavery in their communities. The table below presents links to these customized reports for jurisdictions that today are home to 54 graduate public administration programs in Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island and Vermont, the states in ASPA District 1. The reports are updated dynamically; as new documents are uncovered and added to the database, the information appears in the reports.

While the reports do not directly document material participation in enslavement by the public administration programs involved, they reveal how historical instances of public administration sometimes facilitated or perpetuated enslavement, cases and examples that might be integrated into contemporary courses and curricula. Using the reports, public administration faculty and students may also reveal instances of historical enslavement by the colleges and universities hosting their public administration programs.

These customized reports reveal how historical instances of public administration sometimes facilitated or perpetuated enslavement. These cases are available for academic public administration programs to integrate into contemporary research, courses and curricula.

| Program | State Report | County Report |

| Columbia University, MPA and MPIA | NY | Bronx Brooklyn New York Queens Richmond |

| Baruch College, CUNY, MPA | NY | Bronx Brooklyn New York Queens Richmond |

| Binghamton University, SUNY, MPA | NY | Broome |

| Brandeis University, MPP | MA | Suffolk |

| Bridgewater State University, MPA | MA | Plymouth |

| Brown University, MPA | RI | Providence |

| City College of New York, CUNY, MPA | NY | Bronx Brooklyn New York Queens Richmond |

| Clark University, MPA | MA | Worcester |

| Columbia University MPA and MIA | NY | Bronx Brooklyn New York Queens Richmond |

| Cornell University MPA | NY | Tompkins |

| Fairleigh Dickinson University MPA | NJ | Morris Bergen |

| Harvard University MPP | MA | Suffolk Middlesex |

| Hunter College, CUNY, MS in Urban Policy and Leadership | NY | Bronx Brooklyn New York Queens Richmond |

| John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY, MPA-PPA and MPA-IO | NY | Bronx Brooklyn New York Queens Richmond |

| Kean University, MPA | NJ | Union |

| Long Island University – Post – Brookville, MPA | NY | Nassau |

| Long Island University, Brooklyn MPA | NY | Kings |

| Marist College MPA | NY | Dutchess |

| Merrimack College MPA North Andover MA | MA | Essex |

| Metropolitan College of New York MPA | NY | Bronx Brooklyn New York Queens Richmond |

| New York University MPA | NY | Bronx Brooklyn New York Queens Richmond |

| Northeastern University MPA | MA | Suffolk |

| Norwich University MPA VT | VT | Washington |

| Pace University MPA | NY | Bronx Brooklyn New York Queens Richmond |

| Post University MPA CT | CT | New Haven |

| Princeton University, MPP and MPA | NJ | Mercer |

| Roger Williams University MPA RI | RI | Bristol |

| Rutgers University, Camden MPA | NJ | Gloucester Note: Camden County was formed in 1844 from Gloucester County. Additional records need to be indexed. |

| Rutgers University, New Brunswick MPP | NJ | New Brunswick |

| Rutgers University, Newark MPA | NJ | Essex |

| SUNY Buffalo State MPNA | NY | Erie |

| Seton Hall University MPA NJ | NJ | Essex |

| SUNY, College at Brockport MPA | NY | Monroe |

| Suffolk University MPA | MA | Suffolk |

| Syracuse University MPA | NY | Onondaga |

| The College of New Rochelle MPA | NY | Westchester |

| The New School MSPUP | NY | Bronx Brooklyn New York Queens Richmond |

| The University of Vermont, MPA | VT | Chittenden |

| University at Albany, SUNY MPA | NY | Albany |

| University of Connecticut at Storrs MPA and MPP | CT | Tolland |

| University of Connecticut at Hartford MPA and MPP | CT | Hartford |

| University of Massachusetts at Boston MPA | MA | Suffolk |

| University of Massachusetts, Amherst MPA and MPP | MA | Mansfield |

| University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth MPP | MA | Bristol |

| University of New Hampshire MPA | NH | Strafford |

| University of New Haven MPA | CT | New Haven |

| University of Rhode Island and Rhode Island College MPA | RI | Washington |

| University of Southern Maine MPPM | ME | Cumberland Androscoggin |

| Westfield State University MPA | NY | Hampden |

CONCLUSION

The field of American public administration is considered a modern, technocratic discipline. However, as revealed by the NESRI database, public administration is older than the country and was involved in one of the oldest, most problematic institutions in our nation. This knowledge should serve as compelling inducement for public administration faculty to incorporate historical perspectives of slavery into their academic activities. Those involved with the NESRI project enthusiastically welcome public administration faculty to make use of the database and contribute to its expansion. There is ample room for more scholarship of enslavement and public administration in the Northeast