Note: This project is ongoing; the related article will be updated regularly. The following version is from 2024.

Colleges with colonial (pre-1790) histories have investigated their involvement with slavery during their early years, with the worthy goals of documenting, understanding and possibly making reparations for harm. To date, these studies mostly focus on enslavement activities of college officials living on or near their physical campuses and on the harm inflicted on their nearby communities. Yet the graduates also deserve study, since their greater numbers and geographic dispersal created opportunities to influence many more individuals and communities beyond the immediate neighborhoods of their campuses.

This project cross-references student records from the colonial colleges with those of enslavers in the Northeast Slavery Records Index (NESRI) to identify enslavers who attended these colleges. Additional analyses identify enslavers in the ranks of the colonial clergy, many of whom were alumni of the same institutions.

Why are student enslavers important? Campus officials and faculty members who practiced or condoned enslavement normalized the practice and sent an important educational message to students, who as prestigious alumni brought those values and norms back to their homes or new positions. Thus, slavery on campus could have promoted slavery in both nearby and distant communities. This is particularly probable when the campuses were educating future ministers and religious leaders, as was frequently the case during the colonial era. The students would then be likely to persuasively model, espouse or condone slavery with their congregations and communities.

Colonial College Reports:

Based on our cross-referenced matches, we have developed online reports that include local records of enslavement by college officials or faculty (as reported by the colleges) and regional records by graduates in their home communities. To access a report, select from the list of colonial institutions in the table below.

Our first cohort of campuses is listed here in chronological order of establishment, along with links to NESRI’s locality report for the entire county, the institution’s own slavery reports and examples of their public acknowledgements of enslavement:

Methodology, Limitations and General Findings

NESRI researchers assembled a database of almost 10,000 names of alumni of the above colleges. We matched these against our NESRI dataset on more than 80,000 enslavers in the Northeast to produce reports listing graduates who practiced slavery.

The rules for matching were:

- The names had to match.

- The date range had to be feasible. The enslavement had to take place after the student had graduated and before the death of the matching enslaver.

- The location of the student record had to match the location at the time of enslavement. This required documentation of the student’s residences after graduation.

It is important to understand some limitations of this project:

- A major limitation is the lack of consistent documentation of slavery in the Northeast particularly in the 1700s and early 1800s, except for years when there was a comprehensive census. Most slavery was not systematically documented or retained. Thus, the extent of enslavement is understated for both the general population and among the college officials, faculty and graduates.

- While we have identified enslavement activity in every Northeast colony – way beyond the campuses and their adjacent communities – some graduates returned to places outside the region. NESRI’s systematic list of enslavers does not extend beyond the Northeast, so graduates practicing slavery outside the region would not be included in our reports.

- In many cases, the lack of corroborating information about students after graduation makes it hard to determine whether students and enslavers with the same name are the same person. For Yale, we were able to make matches using online, searchable sketches of early alumni that describe their post-graduate personal and professional lives. In the future, we will be able to identify additional graduate enslavers using similar sketches for Harvard, Dartmouth and Union. These descriptions are available but not easily accessible for cross-referencing. Most other campuses, however, have only names of students listed by graduating years.

While our reports probably understate the level of enslavement by colonial students, the percentages of enslavers in many graduating classes are much higher than in the general population. For example, we identified 6% of the Yale class of 1756 class as eventual enslavers as compared to 2% of the Connecticut general population in the 1756 census. At least 25% of Yale’s 1733 and 1781 graduating classes became enslavers while the statewide percentages for those years were lower. We identified at least 22% of Union College’s class of 1800 as enslavers, when 3.3% of the New York State population was enslaved.

Clergy

Clergy Members and Slavery: The lack of corroborating information to allow NERSI to match graduates and enslavers is not true for a subpopulation: clergy members. Most of the colonial colleges included divinity schools, and graduates who went on to become members of the clergy in the Northeast would have their personal and professional lives documented in The Colonial Clergy and the Colonial Churches of New England and The Colonial Clergy and the Colonial Churches of the Middle and Southern Colonies. Cross-referencing this information with NESRI data allowed us to identify additional graduates with links to slavery. These religious leaders could be expected to be particularly influential in their congregations and home communities as practitioners or proponents of enslavement.

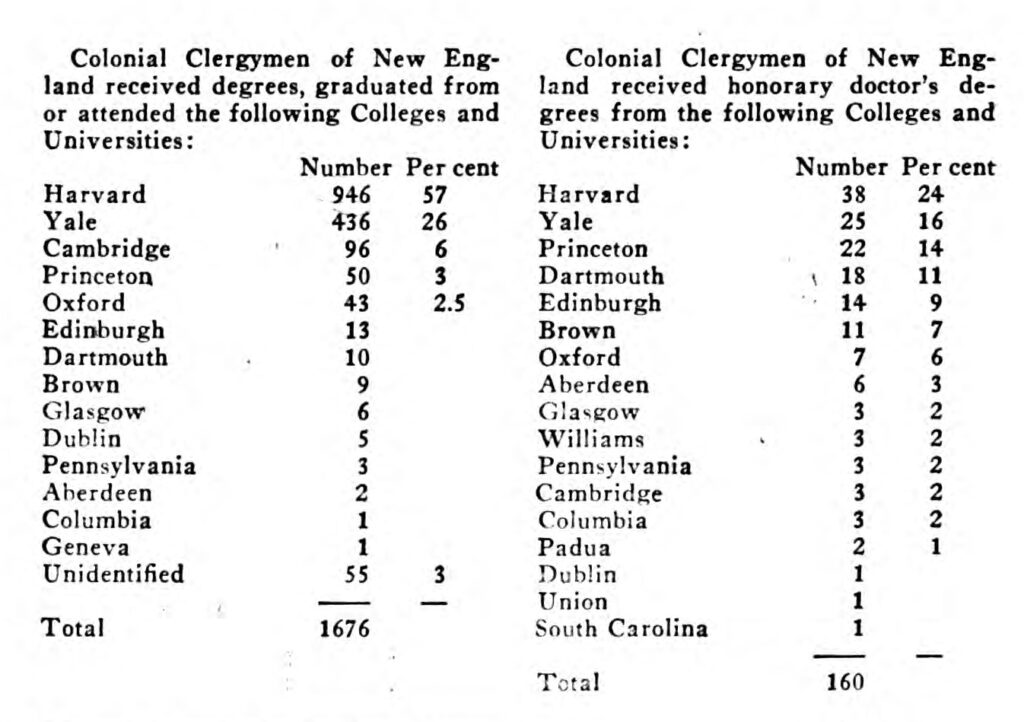

The following tables show that graduates of colonial colleges made up the majority of clergymen in New England.

Divinity Degrees Awarded in New England, by University (Source: Colonial Clergy of New England)

If members of the clergy learned in undergraduate college studies, or in divinity school, that enslavement is normal and not inconsistent with church teaching, they can preach and model these views in their church communities. Another practical reason is the availability of extensive biographical information about members of the clergy, including the colleges and universities they attended, and the churches they served.

ABOUT NESRI

NESRI is an online searchable compilation of records that identify individual enslaved persons and enslavers in the states of New York, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. NESRI indexes census records, slave trade transactions, cemetery records, birth certifications, manumissions, ship inventories, newspaper accounts, private narratives, legal documents and many other sources. The goal is to deepen the understanding of slavery in the Northeast United States by bringing together information that until now has been largely disconnected and difficult to access. NESRI’s database includes almost 100,000 records relating to slavery, most naming the enslaved people and/or their enslavers.

To see what NESRI does, the most direct and simple approach is to click on Find Community or Locality Records. Anyone can identify a place like the name of a Town or County or an entire state, and see a customized report of the enslavement records for the selected locality. For colleges and universities, we uses this page to present tables of officials, students and enslaved people.