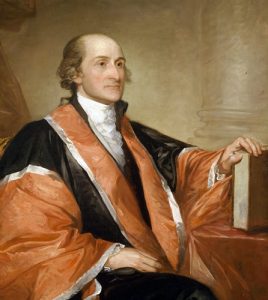

From the portrait by Gilbert Stuart

By Ned Benton and Judy Lynne Peters

Founded in 1965, John Jay College of Criminal Justice was never actively engaged with slavery, as were older educational institutions. Yet, the college is named to honor John Jay, a founding father of the United States, a Governor of New York, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and also, the owner of multiple slaves.

Brown, Yale, Princeton, Georgetown and other colleges are struggling to address or redress their institutional connections to slavery. They are researching the connections and asking whether and when to rename colleges, buildings or programs. The same questions are asked and debated at John Jay College, and our NY Slavery Records Index can inform the inquiries.

In this endeavor, our college can be guided by principles (especially pages 18-23) applied by Yale University as it considered the fate of Calhoun College, named after a United States Vice-President who was a staunch supporter of slavery.

Essentially, Yale considered whether the principal legacies of the person involved are consistent with the university’s mission and values. The concept of “principal legacies” recognized that people can have several legacies that must be balanced, and that the enduring, long lasting achievements of the person should be given more weight.

If we apply this test to John Jay, we must recognize first that he came from a family that owned and invested in slaves. Records from the Slavery Index detail, perhaps for the first time, the extent of the family’s involvement in slavery and the particulars of the individuals enslaved. John Jay owned at least 17 slaves, used their services, rented them out or sold them to others.

Yet, John Jay was also a persistent and effective advocate for the abolition of slavery. The journalist Horace Greeley concluded in 1854 “To Chief Justice Jay may be attributed, more than to any other man, the abolition of Negro bondage in this state.”

How can we weigh these two sides of the man? Can a slave holder be a “fierce advocate for justice?” Here we explore the contradictions of John Jay, the slaveholder and the abolitionist.

Our explorations are informed by our research in this project, and our findings are supported by documentation in our database.

Slaveholding in the Jay Family

There is no evidence that John Jay invested in the slave trade himself, but our index lists his grandfather and father as investors. (Use the tag “JAY” in the SEARCH page to find the relevant records.) Augustus Jay, his grandfather, invested in 11 slave ships delivering a total of 108 slaves to the Port of New York between 1717 and 1732. Peter Jay, John Jay’s father, invested in 7 slave ships delivering a total of 46 slaves to the Port of New York between 1730 and 1733. John Jay purchased a slave named Benoit in Martinique in 1779, and must have arranged for his transport, but there are no records of his ownership in any slave ships.

Several sources document slave ownership by John Jay, himself. In 1783, John Jay appears as the owner of Massey in the “Book of Negroes,” the record of enslaved men and women who escaped their masters and fought with the British in the Revolutionary War. John Jay’s brother Frederick and General George Washington were also listed. Under the terms of the Treaty of Paris that settled the Revolutionary War, these enslaved men were entitled to emigrate as free persons to Nova Scotia.

John Jay’s slave holdings also appear in the early U.S. censuses: 5 in 1790, 5 in 1800 and 1 in 1810.

The names of some of his slaves are documented through letters and other contemporaneous documents:The dates below are the dates of the records.

- Peet in 1771 when he traveled with John Jay to Rhode Island (Stahr p. 238)

- Claas was John Jay’s personal servant in 1775 (Freeman 2005, p.297)

- Massey escaped in 1778 to join the British army;

- Benoit was purchased by John Jay in 1779 and manumitted in 1784. (Morris, 1980, p.705)

- Clarinda, wife of Pompey, was rented out in 1782 (Freeman 2005, p.121)

- Old Mary died in 1797 (Stahr, p. 347)

- Young Mary was to be rented out in 1782. (Freeman 2005, p.121)

- Lewis in 1782 (Freeman 2005, p.121)

- Moll in 1782 (Freeman 2005, p.121)

- Susan in 1782 (Freeman 2005, p.121)

- Peet in another reference in 1782 (Freeman 2005, p.198, 299)

- Yaff in 1790 (Freeman 2005, p.195)

- Pompey, husband of Clarinda, in 1791 (Freeman 2005, p.198)

- Frank in 1792 (Freeman 2005, p. 207)

- Abigail was enslaved to Sarah Livingston when she married John Jay in 1774. She traveled to France in 1783 with the couple when John Jay negotiated the Treaty of Paris. There she escaped, was jailed and later died of disease acquired while in jail.

- Plato in 1794, was rented to Mr. Hartshorne in NYC after misconduct (Freeman 2005, pp. 245-246)

- Phillis, about whom he wrote to his son in 1799 suggesting she be rented out because of misconduct (Stahr, 347)

- Zilpah was rented out in 1809 and immediately bought back, and then manumitted in 1817.

NYSRI Records of Jay Family Slavery

The following table is automatically updated as records are added to the NYSRI database. It lists records that include the “JAY” tag identifying records relating to the extended Jay family. To see a specific record in detail, click on the entry in the “Type” field of the table – the first column.

John Jay as Abolitionist

If John Jay was a slaveholder, as shown above, could he also be a “fierce advocate for justice?” The journalist Horace Greeley concluded in 1854, “To Chief Justice Jay may be attributed, more than to any other man, the abolition of Negro bondage in this state.”

Evidence in support of Greeley’s conclusion lies in the various roles John Jay assumed, even as he continued to own slaves.

He was a founder of the New York Manumission Society in 1785 and he served as the organization’s first president until he resigned to become the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. The society’s mission was to abolish slavery, in general, and to help emancipate enslaved persons, individually. The language of the founding document, probably drafted by John Jay with the assistance of Alexander Hamilton who was present at the organizing meeting, committed the signers in unambiguous terms: “It is our duty therefore both as free citizens and Christians, not only to regard with compassion the injustice done to those among us who are held as slaves, but to endeavor by lawful ways and means to enable them to share equally with us, in that civil and religious liberty with which an indulgent Providence has blessed these States, and to which those, our brethren are, by nature, as much entitled as ourselves.”

Further, John Jay advocated doggedly for the legal abolition of slavery in New York State. When the state constitution was drafted in 1777, he supported a proposal that it abolish slavery. The proposal did not pass.

In 1788, the Manumission Society, with John Jay as President, successfully proposed and achieved legislative enactment of a law baring the removal of slaved from New York state for sale elsewhere. (Foner, 2015, p. 42)

The debate continued throughout the 1780s, without progress. Our records reveal the challenge faced by John Jay and other reformers: in 1790 and 1800, a majority of NY State Senators were slave holders. See our article Slavery and the New York State Senate. In this article we identify the Senators who, based on official records, were slave holders.

But in 1799, now Governor John Jay signed the Gradual Abolition law.

This law did not free persons enslaved at the time of its enactment. But it did free their children, gradually, over a period of decades. This compromise is not what John Jay might have preferred, but it was what he could get out of a legislature filled with slave holders.

After him, John Jay’s descendants continued the fight against slavery.

- His son Peter, as a member of the State Assembly, pressed for laws to accelerate abolition, including one in 1817 that eventually freed those pre-1799 slaves excluded from the earlier law.

- Another son, William, a judge and in New York City and Westchester County was also a fierce abolitionist. As a sitting judge he wrote that he would “withhold his obedience ” to state laws for the return of slaves, and that he would consider it “a duty and a pleasure” to “facilitate the escape of any fugitive slave.”

- A grandson, John Jay II (1817-1894), became a lawyer and took on, without remuneration, many cases involving fugitives from slavery in the southern states who made their way to New York.

In sum, then, what are the principal legacies of the person we honor in the naming of our college? Was he a fierce advocate for justice? With respect to the law and practice of slavery, we have to recognize that he was a slaveholder, in both word and deed. However, our measure of the ferocity of advocacy for justice should also be measured by lasting accomplishment. With respect to the abolition of slavery in New York, no New Yorker was as persistent, politically skilled, and, ultimately, as legally effective as John Jay.