By Ned Benton

To date slavery in New York, it is common to start in the mid 1620s and end in the late 1820s. Our records begin earlier and end later, because we consider enslavement as a functional status enabled and practiced in a range of ways. The functional status of enslavement involves degrees of the following:

- Ownership of the enslaved person, which can be transferred by sale or other means;

- Subjugation of the will of the enslaved person to the owner’s authority;

- Social and legal alienation of the enslaved person and that person’s family and children. Forms of alienation include exemption from legal rights, the extension of enslavement and ownership to children of enslaved people, and the limitation of marriage and family rights.

Records of slavery as a legally authorized activity appear in 1725 in New Amsterdam, and end in 1829 when the process of gradual abolition under the 1799 abolition law and it subsequent amendment and refinement was completed. However, we include records of enslavement starting in 1525 and records of fugitives from enslavement during the underground railroad period prior to and during the Civil War, when fugitives from southern-state enslavement were captured and subjected to re-enslavement under prevailing federal and state law.

Estaban Gomez in 1525

Estaban Gomez sailed with Magellan’s fleet with the early 1500s. He was commissioned by King Charles V of Portugal to search for a northern route to China. Gomez explored and mapped a series of river inlets and bays including the Hudson River which he later called “Deer River.” He did not find the route he searched for, and instead returned to Portugal with 58 indigenous persons to sell as slaves, persons who we might today call native Americans. King Charles disapproved and semi-freed Gomez’ captives, assigning them to various families as servants. It is uncertain where these people were captured from, but it is possible that some came from the area we now call New York. There is no doubt that a slave-ship explored the lower parts of the Hudson River.

Jan Rodrigues in 1613

Jan Rodrigues was a crewman on the Dutch ship Jonge Tobias. When the ship left what is today Manhattan, the captain left Jan Rodrigues behind (Burroughs and Wallace, 1999, p. 18) either because of a dispute or in order to signify possession of the site. Rodrigues did not regard himself as enslaved, but he was a mulatto man who was forced to work for his captain without compensation. (Hodges, 1999, p.6) As the first non-indigenous resident of what is now Manhattan, he acted has a free man. So in the database his record is tagged “FRE” signifying that he was a free person who had previously experienced a form of enslavement.

The African Burial Ground biographical summary explains: “Jan Rodrigues (or Juan Rodrigues, depending upon the source) was the first non-native to settle in New York City. Raised in a culturally diverse household (his mother was African and his father was Portuguese) in the Spanish settlement of Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic, Jan was known for his linguistic talents and was hired by the Dutch captain Thijs Volckenz Mossel of the Jonge Tobias to serve as the translator pn a trading voyage to the Native American island of Mannahatta. Arriving in 1613, Jan soon came to learn the Algonquinian language of the Lenape people and married into the local community. When Mossel’s ship returned to the Netherlands, Jan stayed behind with his Native American family and set up his own trading post with goods given to him by Mossel, consisting of eighty hatchets, some knives, a musket and a sword.”

Emancipations in 1644

The Dutch Colonial Council decided to partially emancipate 11 people from servitude. The record of their decision in 1644 states that the have served the Company for 18 or 19 years. This means that their servitude began in 1625 or 1626.

“We, Willem Kieft, director general, and the council of New Netherland, having considered the petition of the Negroes named Paulo Angolo, Big Manuel, Little Manuel, Manuel de Gerrit de Reus, Simon Congo, Antony Portuguese, Gracia, Piter Santomee, Jan Francisco, Little Antony and Jan Fort Orange, who have served the Company for 18 or 19 years, that they may be released from their servitude and be made free, especially as they have been many years in the service of the honorable Company here and long since have been promised their freedom; also, that they are burdened with many children, so that it will be impossible for them to support their wives and children as they have been accustomed to in the past if they must continue in the honorable Company’s service; Therefore, we, the director and council, do release the aforesaid Negroes and their wives from their bondage for the term of their natural lives, hereby setting them free and at liberty on the same footing as other free people here in New Netherland, where they shall be permitted to earn their livelihood by agriculture on the land shown and granted to them, on condition that they, the above mentioned Negroes, in return for their granted freedom, shall, each man for himself, be bound to pay annually, as long as he lives, to the West India Company or their agent here, 30 schepels of maize, or wheat, pease, or beans, and one fat hog valued at 20 guilders, which 30 schepels and hog they, the Negroes, each for himself, promise to pay annually, beginning from the date hereof, on pain, if any one shall fail to pay the annual recognition, of forfeiting his freedom and again going back into the servitude of the said Company. With the express condition that their children, at present born or yet to be born, shall remain bound and obligated to serve the honorable West India Company as slaves. Likewise, that the above mentioned men shall be bound to serve the honorable West India Company here on land or water, wherever their services are required, on condition of receiving fair wages from the Company. Thus done, the 25th of February 1644, in Fort Amsterdam in New Netherland”.

The First Enslaved Woman: Gracia or Mayken?

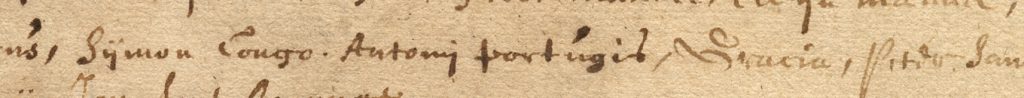

Among the people emancipated in 1644 was a person called “Gracia” which is Portugese for “Grace.” Her name appears on the document:

The name “Gracia” appears in the document between the names Antony Portugal and Piter Santomee.

Gracia may have been the first enslaved woman. However, another emancipation in 1663 was for “Mayken, an old and sickly black woman, to be granted her freedom, she having served as a slave since the year 1628.” This record documents that her servitude began in 1628.

Slavery after 1827

Slavery officially ended in New York 1827. When the Gradual Emancipation law was passed in 1799 it did not apply to persons enslaved at the time, but gradually emancipated children of enslaved mothers born after the enactment of the law. However, in 1817 another law was passed to emancipate the enslaved people from before the enactment of the law in 1799. However, the 1830 census records 75 slaves in New York State. (See US Census Century of Population Growth, p.133) One can also list the owners individually in the dataset by entering Census1830 in “SOURCE” in the Search page. We believe that these are persons born to enslaved mothers some years after 1799 who were still completing their years of slave-like service required under the emancipation law.

Slavery also continued to exist in New York in other ways.

Out-of-State Slaves Temporarily Visiting: The 1817 law that eventually emancipated NY slaves in 1827, also permitted slave owners to bring enslaved people into New York State for up to 9 months, effectively recognizing enslavement based on the laws and practices of other jurisdictions.

Fugitives: Fugitive slaves would be captured and be formally adjudicated by New York courts, under federal and state law, for return to the state the fled from. Agents representing southern plantations search for black persons resembling fugitives. They would take them south furtively, or, take them to NYC’s Court of Special Sessions, presided over by former slave holder Richard Riker and his associates known as the “Kidnapping Club.” We have assigned the tag “RIKER” to records of such cases.

Slave Ships: While New Yorkers were not allowed to own slaves, the Port of New York allowed slave ships to anchor and restock. A Federal court case – U.S. v. Joas E. de Souza dated 12/16/1838, by Judge Thompson of the United States Circuit Court, found that a ship was permitted in (in this case in NY Harbor although the court was Federal) to carry slaves as long as there was no intent to sell or transfer them.