By Scarlett Hoey & Robert Hummel

In discussing the colonial history of Worcester County, we must first acknowledge that the people of Nipmuc Nation and their allied tribes, past and present, have always lived on the land that is now called Worcester, Massachusetts. As colonial settlers moved across New England in the 1600s and 1700s, they committed acts of genocide, slavery and forced removal of Indigenous people. Yet despite these atrocities, the Tribal Government and Citizens of Nipmuc Nation have continued to be active members of the community through to the present day. You can learn more online at www.nipmucnation.org/. The Native Land Digital map (https://native-land.ca/) provides resources to learn more about the lands where you reside and inhabit.

“Why do we avoid confronting hard history?” asks Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Associate Professor of History at Ohio State University, in his TED Talk. He cites Regie Gibson, a literary performer and educator, when he says “Gibson had the truth of it when he said that our problem as Americans is we actually hate history. What we love is nostalgia. Nostalgia. We love stories about the past that make us feel comfortable about the present. But we can’t keep doing this.”

Worcester, Massachusetts, recently celebrated the 300th anniversary of becoming a town (Tercentenary 2022). As part of this celebration, the city is looking back on its history. A frequently overlooked part of Worcester’s past is its utilization of enslaved labor and its dependency on the transatlantic slave trade in building the wealth of the region. While uncomfortable for some, thinking critically about these past local injustices is an aid in advocating for a more just future by understanding history and not just nostalgia.

Exploring the history of Worcester County

Motivated by this, one of us (Scarlett Hoey), began to focus her artwork and photography on the history of enslavement and resistance in Worcester County. The first series of artworks was presented in 2022 at ArtsWorcester (https://artsworcester.org/exhibits/material-needs-2022/scarlett-hoey/). Additional work in this series is part of a show at the Worcester PopUp gallery running June 28 to July 9, 2023. (https://tockify.com/livtestcal/detail/281/1687968000000).

In researching this history for these artworks, we found that enslavement in Worcester County can be seen in many different places, such as legal documents, census records, and even physical markers like gravestones (pictured below, Eden London). Each of these pieces of evidence can be further investigated, questioned, and considered as part of broader interpretation of the history of Worcester County.

The goal of the artwork series and in uploading our research records to the NESRI database is to encourage discussion and provide resources for educators and interested individuals to learn more about their town. Some of the recurring themes we encountered are discussed below.

We would also like to acknowledge that many others have also conducted this research both locally and on a larger scale. Further acknowledgements are contained at the end of this article.

Eden London, Old Centre Cemetery, Winchendon, Massachusetts

Revolutionary War Veteran Enslaved by Joseph Moores, Samuel Bond, William Williams, John M’Cluster, Joshua Holcomb, William Bond, Jonathan Stimson, Thomas Sawyer, John Ingersoll, Esq, Mr. and Mrs. Oliver Partidge, Thomas Cowdoin, and Daniel Goodrich,

digital inkjet print, 10″ x 8″, 2022

Discussions of slavery in the United States often focus on plantation slavery in the southern states, while Massachusetts and its 19th century abolitionist residents such as Abby Kelley Foster are presented in opposition to the enslavers of the South. In Worcester, Abby Kelley Foster’s home, now a National Historic Landmark, is called “Liberty Farm” in reference to its role in the Underground Railroad.

However, discussion of slavery in Worcester cannot stop at this time period. In fact, Massachusetts Bay Colony was the first of the American Colonies to legally recognize slavery. In 1641 the Body of Liberties legal code permitted the enslavement of “lawful captives taken in just wars, and such strangers as willingly sell themselves or are sold to us” (https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/slavery-and-law-in-early-ma.htm).

Even prior to this, shipbuilding in Massachusetts created vessels used in the transport of people who were enslaved. The Marblehead Museum describes how The Desire, built in 1636, was used to carry goods and people who were enslaved both to and from the West Indies. https://marbleheadmuseum.org/ship-desire/

The 1754 Slave Census of Massachusetts documents at least 88 people over the age of sixteen who were enslaved in the County (https://primaryresearch.org/slave-census/). We will never know the true extent of how many people were enslaved in Worcester County because these census records did not include minors and not every town reported. And, while census information is an important primary source, data cannot replace the acknowledgment that each number signifies a human being.

Scarlett Hoey

The Massachusetts Slave Census (1754)

digital inkjet print, 11″ x 14”, 2022

Resistance

Resistance against enslavers has always existed. While many colonial records were created from the perspective of the enslavers, we can still see evidence of the strength and resistance to enslavement by those individuals who were enslaved. This can be seen in self-emancipating [fugitive] slave advertisements, freedom-seeking petitions and court cases, and letters of friendship between people who were enslaved.

The Quock Walker legal case is one such example of resistance. Quock Walker was enslaved in Barre, Worcester County, Massachusetts, and, after a promise for his eventual freedom went unfulfilled, self-emancipated and then sued for his freedom. The resulting court cases led to his freedom being legally recognized. The story is often simplified to say that this case ended slavery in Massachusetts. However, it is better seen as one of several events which gradually ended slavery in the state, as no legislative action or law abolished slavery in Massachusetts until the 13th amendment to the U.S. Constitution ended slavery nationwide.

More about Quock Walker can be found here: http://www.longroadtojustice.org/topics/slavery/quock-walker.php & here https://www.mass.gov/guides/massachusetts-constitution-and-the-abolition-of-slavery).

Elizabeth Freeman, of Berkshire County, is another person who was enslaved and fought through the courts for her freedom: https://thetrustees.org/content/elizabeth-freeman-fighting-for-freedom/.

Evidence also exists of a different kind of strength and resilience of enslaved people in the County. Surviving correspondence between Obour Tanner and Phillis Wheatly Peters shows the enduring friendship the two women maintained throughout enslavement and Peters’ manumission. Obour Tanner was enslaved in both Worcester and Newport, R.I. by the Tanner family. In 1809, as a free person, Obour Tanner co-founded the African Female Benevolent Society with Sarah Lyna in Newport, RI (https://www.colonialcemetery.com/african-names/). Imagining the Age of Phillis is a series of short films based on the poetry of Honorée Fanonne Jeffers commissioned by Revolutionary Spaces which touches on the friendship between these two women (https://www.revolutionaryspaces.org/imagining-the-age-of-phillis/).

Additional forms of resistance are documented in newpapers such as the Massachusetts Spy, Boston Post, and Boston Gazette which contain numerous advertisements placed by enslavers requesting the re-capture of freedom-seeking individuals. Many of which were placed by enslavers living in Worcester County.

Scarlett Hoey

Former Site of Worcester County Courthouse & Civil Trials of Quock Walker, Barre (Rutland District)

digital inkjet print, 8″ x 10″, 2022

Wealth and power

Many of the enslavers in Worcester County held positions of wealth and power in their communities as government officials, reverends, military officers, and merchants. These individuals often feature front-and-center in a commonly told town’s history, with their involvement in slavery usually omitted.

For example, Governor Moses Gill of Princeton, Judge John Chandler, and Sheriff Gardiner Chandler of Worcester were enslavers who held government roles in the County.

Documentation, in diaries and vital records, show that many church leaders were also enslavers including Rev. Humphrey of Athol, Rev. Goss of Bolton, Rev. Prentice of Grafton, Rev. Harrington of Lancaster, Rev. Frost of Mendon, Rev. Whitney of Petersham, Rev. Eaton of Spencer, Rev. Parkman of Westboro, and Rev. Webb of Uxbridge.

Another example is Aaron Lopez of Leicester. Lopez was a prominent merchant, once the wealthiest person in Newport, Rhode Island, whose property was used for the first building of Leicester Academy. Additionally, Lopez was owner or co-owner of ships that participated in at least 21 slaving voyages (https://www.slavevoyages.org).

Enslavers in the region also held military titles. Captain Daniel Henchman of Worcester is considered one of the founders of the town of Worcester and is recorded enslaving several individuals. Major Samuel Willard of Lancaster, Captain Nathaniel Allen of Shrewsbury, Captain Lyon of Leicester, Captain Thomas Cheany of Dudley, and Captain Stephen Maynard of Westboro are all recorded as enslavers.

Colonel Timothy Bigelow is recorded, in a 1771 tax inventory, as holding two “servants for life.” In a letter to his wife during the Revolution, he insisted she not sell their enslaved servant, Pompey, lest he be accused of fighting for liberty while selling slaves. It is not known by us when or if the individuals he enslaved ever experienced freedom.

Scarlett Hoey

Near the Former Site of Aaron Lopez’s Home and Store, Leicester Academy, Leicester, Massachusetts

digital inkjet print, 8″ x 10″, 2022

Complicity among non-enslavers in 18th and 19th Century Massachusetts

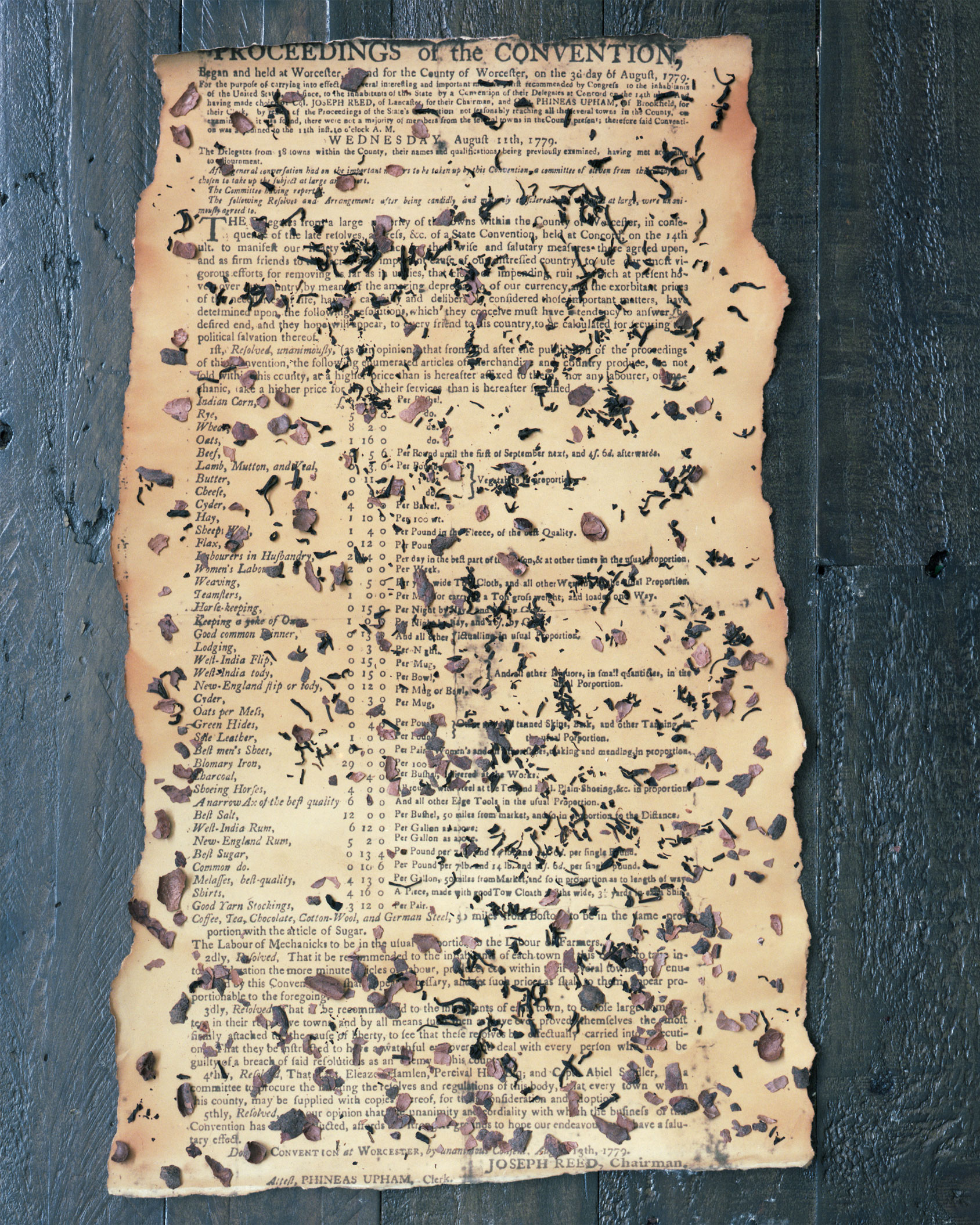

Beyond directly enslaving others, many in the region were in one way or another complicit in the transatlantic slave trade. The 1779 Worcester County convention established prices for goods produced both locally (butter, wheat, cheese, cyder, chocolate) and globally (West-India Rum, sugar). Rum, molasses and sugar were all commodities exchanged as part of the triangle trade.

Additionally, Dr. Jared Ross Hardesty, an historian from Connecticut College, believes, “That no chocolate sold in colonial Boston was free of connection to enslaved labor.” Boston’s Old North Church provides an educational curriculum on this topic: An Exploration of Trade, Production, and Slavery: Chocolate and the Old North (https://www.oldnorth.com/cacao-colonial-chocolate).

The Worcester Art Museum in its collection includes objects used in the consumption of these triangle trade goods, such as sugar tongs (https://worcester.emuseum.com/objects/7751/sugar-tongs) along with portraits of people who profited from the systems. In 2018, the Worcester Art Museum began adding labels to many such portraits with historical research discussing the subject’s ties to slavery (https://hyperallergic.com/439716/can-art-museums-help-illuminate-early-american-connections-to-slavery/). Many museums are moving towards incorporating more expansive wall labels for their portrait galleries and a few have started to add more context to their decorative art collections.

Many 19th century industrial businesses in Worcester County sold their goods (shoes, hats, and farm-tools) to Southern plantations or utilized products produced by enslaved labor (cotton). In the chapter Slavery Has Lifted Up Her Voice in Our Streets from the 2009 Worcester Historical Museum’s book, Landscape of Industry: An Industrial History of the Blackstone Valley, Ranger Chuck Arning writes, “The Blackstone Valley remains an example of this national conflict between passionate abolitionists and their fight to end slavery versus the interests of the Southern planation economy and the northern textile mills to maintain the system that allowed New England to earn their keep.” The wealth, in Worcester County, generated by these industrial businesses can be directly linked to benefiting from the continued southern practice of enslavement.

Scarlett Hoey

Proceedings of the Convention of Worcester (1779)

digital inkjet print, 14″ x 11″, 2022

Further work and acknowledgements

This work is ongoing. Our contribution is but one in the long history of discussion and interpretation of enslavement and freedom via histories, museum exhibitions and programming, artworks, books and doubted records. Although there are too many to name, our interest and gratitude would have us acknowledge the following: Lorenzo Johnston Greene, Elaine MacEachern, Alexandra Chan, George Quintal, Jr., Cheyney McKnight, Marieke Van Damme, Joseph McGill, Kristin Gallas, James DeWolf Perry, Janette Greenwood, Thomas Doughton, Wendy Warren, Meadow Dibble, Erika Slocumb, Staci Hanscom, Britany Cook, Meghan Gelardi Holmes, Marla Miller, Christy Clark-Pujara, Rebecca Hall, Ibram X. Kendi, Marjory Gomez O’Toole, Patricia Q. Wall, Kyera Singleton, Carl Robert Keyes, Evelyn Dube, Seth Rockman, Brigitte Lewis, Tara A. Bynum, Emily Ross, Catherine Adams, Elizabeth H. Pleck, Martha S. Jones, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Anne Farrow, Joel Lang, Jenifer Frank, and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham. Each piece of new evidence, some in plain sight, can further understanding and enable us to make progress towards a more just future.

One of the ways this exploration continues is through an upcoming exhibit, In Plain Sight & Redemption, at the JMAC PopUp Gallery in Worcester, June 28 to July 9, 2023 (https://www.jmacworcester.org/). In this two-person exhibit, artworks by Scarlett Hoey and Jennifer Davis Carey focus on people who were enslaved within and outside of the Worcester area.

This works builds on a prior project supported by ArtsWorcester. In addition to support in part by a grant from the Worcester Arts Council, which was made possible with American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) Funding from the City of Worcester. The Worcester Arts Council is a local agency, which is supported by the Mass Cultural Council, a state agency.